Princess Margarita of Romania tells how 'In August last year, I resigned my job. The UN machine would keep turning without me.'

By PRINCESS MARGARITA OF ROMANIA

The last few months have seen the history of Europe telescoped; my own personal history, too. A year ago I had an absorbing job in Rome, working for part of the United Nations, dealing with the problems of poverty, famine relief and underdevelopment. But I was constantly thinking of my own country, Romania. All my life had been coloured, overshadowed by its history and people, by its pain and suffering. It was a land forbidden to us, and yet it was our home. So for me it had always been mysterious and yet familiar. For the majority of people in the West it was a hidden land. No one spoke of it, many had hardly even heard of it. Yet now the veil of silence was starting to lift. Western public opinion was at last being aroused by pictures of smashed buildings as villages were bulldozed into dust, communities and families were torn apart and culture was destroyed.

In August last year, I resigned my job. The UN machine would keep turning without me, but Romania had only one King Michael, and he was alone. The days after the uprising in Timisoara - when the whole country, led by the young people, surged into the streets and fought for their freedom - were agonizing. It was a terrible struggle between good and evil. There were the reports of thousands killed, and in us there was a feeling of raw shock and pain.

Unbelievable destruction

For the first time in my life we saw live television pictures of Romania: the crowds in the streets, tanks, fighting, the roads, the trees, the towns. It was like the tearing away of a veil. Then in January, I went to Romania for the first time. We've never had a real home anywhere else, because Romania was our home, and yet it was like going to a forbidden planet. The preparations for the visit absorbed me fully, but the day we left, I was seized with anxiety: What would it be like? Would they let us in? What would people feel about us? Would I be up to it? I went to my room and knelt in prayer. I felt that I was a part of my father returning from exile. It was an awesome responsibility and a great joy at the same time.

I found a terrible landscape: everything seemed to be a dirty grey. The physical, economic and moral destruction was unbelievable. At the airport, there was such a crowd that we couldn't get off the plane - some smiling, some scared, many curious, some calling for my father. It was a strange feeling. We were at home, and yet there was this dehumanized layer of communism like a grey cloak over the natural warmth and culture and history of the people.

We visited hospitals, orphanages, old people's homes, villages; we laid wreaths at the memorials to those who died in the revolution. In the 'new villages' where people had been rehoused in miserable concrete blocks, the destruction, despair and poverty were total. Children in slippers followed us in the snow. People wept as they showed us pictures of their destroyed homes. In Bucharest, we met hundreds of people. Some had walked miles to see us, others had paid a month's salary to come to the city; all brought gifts. They had nothing, but they still wanted to give. Each one had a hurt, a pain to share, many had suffered years of prison. There were many tears. We realized that for some we symbolized a better past, and the hope of a better future.

I discovered the desperate need for a renewal of moral, spiritual and human values. People couldn't even look straight at each other, couldn't speak openly together. They had forgotten how to laugh. So much of the culture and the history had been destroyed. What had people been able to do with their free time? Sit and talk? But they couldn't, for fear of spies and informers. Suspicion is the most terrible disease. So now there is a crying need for rebuilding the rich culture that has been wiped out, the villages, the communities, the churches, the schools - but also the pride and dignity that have been annihilated. There's no sense of tolerance, and democracy needs tolerance, and the ability to negotiate, to see the other person's point of view.

Middle generation

These values have been foreign to the recent past, but now many are hungry for such values, for culture, for their history. You feel this most in the young, the students who made the revolution, and in their grandparents, but there is a middle generation missing - they sold out, many of them. Now people are flooding back into the churches. It was so moving to see the old teaching the young to make the sign of the Cross. We have to help build links between people, to help them find courage and faith in the future, for themselves and for our country. It is hard for them to believe that the future depends on the best efforts of each one.

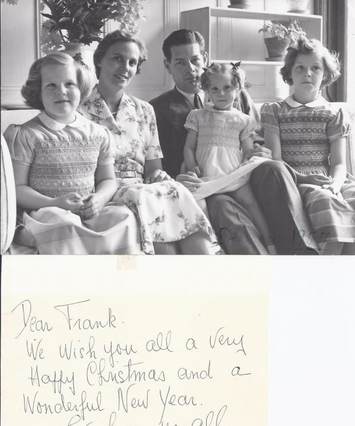

Whether or not my father returns to the throne, he has a role as an incarnation of the Romania that stood against the extremes of left and right, the best of our past. That is a shining light, and we as a family can help to keep that flame alive, to give people a link with their past, and hope for the future too, and a strong link with the rest of Europe - we are a European family. There are so many quarrels and divisions between personalities.

Perhaps we can help people to stand up for what is right. The recent elections change little: this deeper task remains, unchanged, for all those who truly love Romania.

Princess Margarita is the eldest daughter of the exiled King Michael and Queen Anne of Romania.

English