(written in 1990)

'One man one hundred per cent committed to God is better than 99,000 ninety-nine per cent committed.'

So said Peter Howard. And he lived that commitment as fully as anyone I've ever known.

He died exactly 25 years ago. I remember the day well. It was my birthday. I heard the news in London after an evening play, and got home to Oxford late. There was a telegram from Peru, where he and his wife were making an official visit. It said: 'Happy Birthday, Peter and Doë.'

I shared a room with Peter Howard at the Connemara Hotel, Madras, India, in 1953. The lizards on the wall, I remember, seemed rather large and frightening, but I soon got used to them. I rose each morning at six for a quiet time. Peter rose at four for the same purpose, and to begin his letter-writing. The rest of the day was full of engagements, except that about 2.30pm he had a nap and then wrote his wife - each day.

It was for me a remarkable two weeks.

All-outers are not easy people. They remind me of Gothic architecture - dynamic, attractive but not always symmetrical. There was nothing cut and dried about Peter Howard. He was unexpected, unpredictable and very, very, very good company.

He used to say that being honest does not make you right. But it does mean that you live in the light and let in the light, and the light is God. Leadership, in his mind, meant the complete readiness to make mistakes. In fact, he said, the more all-out you are, the more mistakes you're liable to make, because you're not God. 'I reserve the right to be wrong,' he said.

He wrote about 15 plays. Personally, I find all of them good and some great. I remember seeing The Hurricane and The Ladder for the first time as a double-bill. That remains for me the most powerful theatre evening of my life. These plays are being produced today but I would also say that they are waiting to be rediscovered.

'I write with a message,' he said, 'and for no other reason. Do not believe those who say the theatre is no place for a man with a message of some kind. Some writers give their message without knowing they do it. A man who writes as if life had no meaning is the man with a strong message. My plays are strong propaganda plays. I write to give people a purpose. The purpose is clear. The aim is simple. It is to encourage men to accept a growth in character which is essential if civilisation is to survive. It is to help all who want peace in the world to be ready to pay the price of peace in their own personalities. It is to end the censorship of virtue which creates a vicious society. It is, for Christians, the use of the stage to uplift the Cross and make its challenge and hope real to a perverse but fascinating generation.'

It was once said of Henry Drummond that 'his love had the temper which is jealous for a friend's growth and had the nerve to criticise'. Peter had that rare quality and encouraged you to care for him in the same way. This is a delicate and dangerous expression of love. Christ made enemies because He told people the truth. Saying nothing is much easier and costs nothing: but the result is that people easily choose the second-rate road in life when a spur in the flank might have sparked greatness.

'Passion is good,' said Howard, 'but passion needs firm friends at its side to see if it is passion guided by God. If we live that, I believe, "Am I therefore become your enemy because I tell you the truth?" (St Paul) could become the normal salt of our life.'

In 1950 he wrote this: 'I have been thinking a lot about youth. My heart is very much with them. I feel that many of them, if not most, have never known this deeper experience of the Cross where their self-will is handed over. What you get is a steely philosophy, garlanded and rendered charming by the attraction of youth, which has made up its mind to have its own way on many points, and yells "Dictatorship!" if anybody tries to stop it. Adults must not be allowed to stifle, smother or stereotype youth. Equally we must change this spirit in some of the young who think it is rendering the world a pioneering service by rebellion and brashness.'

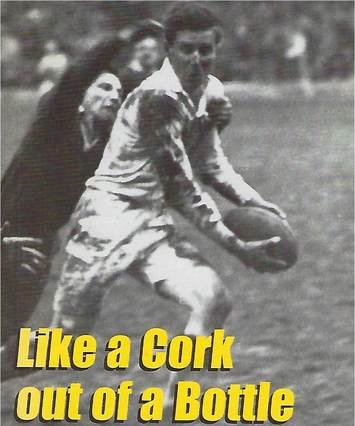

I have not mentioned his international rugby - a quite extraordinary achievement with his lame leg, his 15 books, his remarkable journalistic career, his effectiveness on the international scene, and the deep love for his family which made all the more poignant the sacrifice of being away from them so much. But you can read Peter Howard: Life and Letters, the absorbing biography written by his daughter, Anne Wolrige Gordon.

To a conference of American Indians in Albuquerque, New Mexico, he said: 'To meet the needs of modern man takes clean hands and a pure heart. It takes pure hearts because the problem is not colour. It is chastity and the passionate commitment, "Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven," so that we live, speak, breathe, work, sweat and fight to help God's will be done in the affairs of men.'

He read and re-read The Greatest Thing in the World, Henry Drummond's collected addresses. Drummond wrote about the farsightedness of 'the statesmen of the Kingdom of God', and Howard underlined that passage.

He was surely such a statesman himself.

I remember him with huge gratitude. He had a vision for me far bigger than anything I'd thought of. I remember his courage, his encouragement, his kindness and his blazing faith. I recommend people who did not know him to discover him. I was lucky enough to know quite well one of the great spirits of the century.