When I took the Diploma of Education at Oxford, I first met the writings of Sir Richard Livingstone, classicist, educator, and vice-chancellor. I have never seen the purpose of education expressed more arrestingly.

Here are some of the points that Livingstone made in his book, Education for a World Adrift (1943):

For hundreds of years the people of the west have been walking through country signposted and fenced by the precepts of a religion which they accepted. The great majority followed the beaten track and kept within the fences.

Now we live in a different world. The road is still there. But people have broken through the fences, defaced the signposts, and questioned the accuracy of the map. We are back in the moral confusion of the Greek Age of the Sophists.

All we need are firm standards and a clear philosophy of life which distinguishes evil from good, and chooses good and refuses evil.

The quality of civilisation depends on its standards, its sense of values, the idea of what is first-rate and what is not.

Aeschylus, Plato, Shakespeare and Dante of all Europeans have seen furthest and reached highest, and best reveal the greatness of human nature. They meet some permanent need not only of their own epoch but of all time.

The true name of education is a discipline by which a man from first to last hates what he should hate and loves what he should love.

Livingstone quotes Plato, 'The noblest of all virtues is the study of what man is and how he should live,' and goes on to quote the early 20th century philosopher, A N Whitehead, 'Moral education is impossible without a habitual vision of greatness.' Livingstone adds: 'No profounder statement has been made about education since Plato.'

I remember Churchill's phrase: 'The rut of inertia, the confusion of aim and the craven fear of being great.' In his Great Contemporaries (1937), he wrote: 'Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities because it is the quality which guarantees all others.' I suggest that the root of greatness is unselfishness, the quality that enables people to grow around you and not diminish.

There is an old saying that if you're 5% self-centred you are ineffective, 15% self-centred you are unhappy, and 85% self-centred you are locked up in an asylum.

One of the great educators of the 19th century was Edward Thring, headmaster of Uppingham School, Rutland, 1853-1887. I went to the same school half a century later, and his statue looked at us in the school chapel.

In 1862 he wrote: 'I feel jaded, badgered, faithless and hard, I long to plunge into some fierce reality instead of holding on in patience and power, instead of the long restraint.' What a splendid expression, 'the long restraint' - surely one of the ingredients of greatness.

He said: 'Every step of ground has been won inch by inch.'

Here are some of his remarkable observations:

The business of a school is to train up men for the service of God.

May God make me a prophet.

Love of truth must be set on its throne if any nation is ever to be really educated.

Nothing is more obtrusive than obtrusive religion.

Of all the problems which the training of boys present to parents and teachers, the one for dealing with impurity in thought and word and deed is the most perplexing. I suppose everyone is acquainted with the current lies about the impossibility of being pure. The means under God in my own case was a letter from my father; a quiet simple statement of the sinfulness of the sin, and a few of the plain tenets of St Paul saved me. A film fell from my eyes at my father's letter. All fathers ought to write such a letter to their sons.

The value of good reading aloud has never been fully recognised.

Genius is an infinite capacity for work growing out of an infinite power of love.

For the young the best is just good enough.

Music is the only thing which all nations, all ages, all ranks, and both sexes do equally well. It is sooner or later the great world bond, the secular Gospel.

It was Thring who pioneered the first full use of music in schools. But, above all, he will be remembered for being the first to assert boldly that the dull boy has as much right to have his power fully trained as the boy of talent. 'Everybody can do something well,' he said.

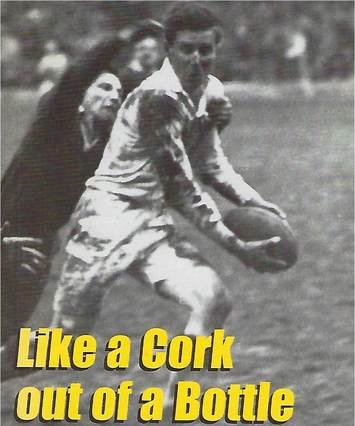

'Life' was the word most on his lips, and his aim 'the right love and the right hate'.