lf Philips of Eindhoven had a motto, it should be 'All Mod Con'. Philips will freeze your food and shave your beard, toast your bread and record your LP, show your films and light your streets, take your X-ray; wash your clothes and supply your radio, video or TV – and much, much more.

But why, when other big-name electrical firms in Europe and America lag behind, should Philips remain among the front-runners? Why can they match the dedication that has produced the Japanese electronic miracle?

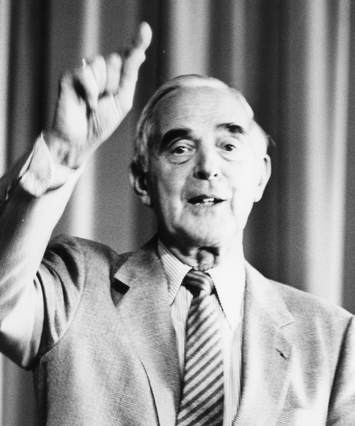

lt might seem unfair to single out one man when so many engineers, scientists and salesmen have so devotedly built up Philips' morale and standard of excellence. But it would be unrealistic not to highlight the contribution of Frits Philips who, in or out of prison, held Philips together during the Nazi occupation, rebuilt it after the war and was its President during ten years of unparalleled expansion in 50 countries. His colleagues have readily honoured him for his judgment and courage, his enthusiasm and flair.

Frits’ uncle Gerard started making light bulbs in 1891 and his father Anton expanded the commercial side of the firm. Frits graduated in engineering and after working on the shop-floor of tool-rooms in Coventry and Paris he joined the firm in 1930.

The Depression hit them hard. Orders dried up. But Frits developed film projectors, sodium lamps and other new products and in '35 was appointed Assistant Managing Director. Philips were first in the field with TV – as early as '37 they were selling them in Britain!

By 1939, when he became joint Managing Director of the workforce had built up from 16,000 to 45.000. One of his responsibilities was labour relations. For years the Philips company had been against trade unions and there were few members among the employees. Frits had talks with union officials. ln 1941, when the Germans had invaded and were dismantling the Dutch trade unions, Frits made a 'gentlemens agreement' with seven trade unions, 'undertaking in principle, to conclude collective agreements’ after the War.

During the occupation, with many senior colleagues in exile, his home and factory blitzed by allied bombs and, (when be wasn't in prison) with a German controller looking over each shoulder, Frits managed to outwit the authorities and deny them equipment for military purposes. He became quite a folk hero.

The Liberation in 1945 was profoundly welcomed, but the reconstruction of Philips posed immense problems – Iack of food, houses and raw materials. Frits set about be task with renewed conviction. In 1946 the Board took the significant step of including in its Articles of Association a new paragraph – 'the Company shall aim at a long-term welfare policy and maximum useful employment. . . .' Three years later Philips of Eindhoven signed a labour agreement with 15 trade unions.

By 1948 production was back to the '39 level. Two years later it had doubled again.

There was a new autonomy in the Philips overseas operation, now manufacturing in 50 countries and selling in 20 more. They were merely required to report direct to the board of management, This called for the building of a world-wide network of personal relationships which Frits did with great skill and sensitivity.

ln 1961 he became President. During the next ten years, as TV and transistors transformed the world electronic industry, Philips' turnover multiplied four times and the work-force rose from 226,000 to 376,000. Philips' 'work-structuring' was a courageous innovation in the '60's. In place of the mindless monotony of the old assembly lines, they organised groups of 4-12 employees to build complete TV sets, with minimum supervision. It raised costs, but it created much greater work satisfaction.

On his retirement the Queen of the Netherlands awarded Frits the Gold Medal for Enterprise and Ingenuity. Since then he has been Chairman of the Supervisory Board.

What is Frits Philips' secret? How did he build the 'japanese-style' commitment into a firm which shared most of the social divisions of European industry, and maintain in as a world leader?

Basically it is because he takes time to understand how people feel. I have often seen him sitting with workers from France, India or Britain as they poured out their grievances.

Of course he had experience on the shop floor – but so have other employers. 1t was possibly his experience in prison that made the difference. Behind German barbed wire he had long talks will trade union men about their mutual hopes and dreams. After the War they translated them into reality.

As well as concluding the trade union agreement, he found ways of keeping personal touch with the work force, such as meeting the Works Council for a 'fireside-chat', with questions to and fro. Outside the plant Eindhoven employers and trade unions met and planned to restore Holland's prosperity. Each year the full Board of Management meet the trade unions for a conference. Frits also took a leading part in the nationwide Foundation of Labour, where president of employers’ federations and the trade unions discuss current issues and advise the Government.

Frits Philips has chaired many sessions on world industry at the MRA conferences at Caux. And when he speaks men and women from many countries and background are moved. He is aiming at something beyond razors and lasers, beyond even the normal business parameters of expansion and profitability. Here is a multi-national boss, who has himself accepted an 'inner revolution' and who believes –

- that industry is meant to serve the world community – to ensure that food, work, shelter and faith are available for all people everywhere.

- that industrialists must be responsible not only for next year's balance-sheet but for the survival of the basic framework of values in which we operate.

- that industrialists can begin by setting their own house in order and by making consultation, participation and communication work.

- that the original Creator of Light can also direct the steps of every man, woman and child.

英語