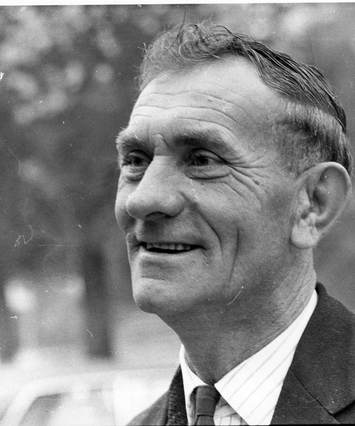

Reggie Holme - Narrator: This is another in our series ‘Faith that shapes the future’ and I am talking to Jack Carroll of Bristol. Jack, tell us a bit about who you are and a bit about your family:

Jack: My name is Jack Carroll. I belong to a well-known docking family. When I say a well-known docking family, my father was a docker. My grandfather was a docker and my great-grandfather was a docker. I am the eldest of 4 sons, all dockers. To be a docker, we feel you have got to be born into the industry. Years ago, it was impossible to become a docker unless your father, your uncle, your grandfather or some relation in the family worked at the docks. The docks was a very happy family because it was the families, the sons, the nephews and the cousins from all these families that made up the docking force. So, we are a great docking family.

I can remember the time when it was real poverty. When my father was first a docker it was about 30 shillings, or £2/week sometimes, that he brought home to keep the house going. I had 4 brothers and 2 sisters altogether, so it was a real struggle. It was real poverty days them times. Very often I used to have to sell newspapers. On a Thursday we used to have what they called a cattle market day, where the sheep and the cows were sold. I used to make it my business on a Thursday to go to that cattle market and drive sheep and cows, very often with no boots on - you can imagine what it was like walking around after driving cows and sheep with no boots on - just to earn a few bob to help to keep the family going.

I had a very difficult education. I was always trying to do something for my mother to help bring money into the house The only time I used to like going to school was on a Friday because I would be picked for the football team.

I left school at a very early age - before I was 14 years of age. I felt this was a must because we needed the money and the quicker I could go to work the easier it would be for my mother to help run the house. I first went into a grocer’s shop. I was there a very short time then I went to a factory. I left that factory and went into a factory where they made leather for boots and shoes. I stayed there right up till it was time for me to become a docker. I became a docker at 20. It was very hard to get work, being a young docker, because these ships used to come in and employ the people that they knew, the old dockers. Then the young dockers very rarely had work until we became established. When I say established I mean working for a stevedore who could see that you were either the son of one of the old dockers or the grandson. Then you got known and, of course, your work as well was judged. You had to work hard to become a regular dock-worker.

The casual labour system at the docks came in about 1925 - I think the quicker I get that out of my mind the better because casual labour in them days was what we call a rate race. There was a kind of control point where you had to report for work in the mornings. You had to report every morning for work and the employer would select the people he wanted. It was just like selling your body to the highest bidder, as regards employment. The price we were paid for working in them days was 12 shillings a day. Now you can imagine on a Monday morning when you went to work, you were selected for work and your shift finished at 12 o’clock. You would only get 6 shillings pay for that. Out of that 6 shillings you would get a 1/6d health and a 1/3d unemployment stamp, so you can imagine that you were only working for a few bob and that might be the only work you had for the whole week. You can imagine the struggle to make ends meet.

It made me very bitter and I grew up to be one of the militant men of the port. I became interested then, very interested, in the trade union movement. I fought within the trade union movement to answer some of the problems that faced us in the docks. I was not an officer in the union - I was one of the unofficial union officials, not on the union side but on the side of an unofficial body which was operating in many ports of the country. I was elected by the rank and file as an officer of the unofficial liaison committee. This first came about through Mr. Jack Dash, the London communist. He was the first man to form these unofficial liaison committees in many ports of this country, During the strike in 1965 of which I was one of the leaders, I was met by Jack Dash and he invited us to London. There I learnt many things about how to operate in the port unofficially and yet not get myself into trouble with the TGWU.

This strike was in September 1965 in Bristol, when we had a ship come into Bristol called the Bristol City. Now this ship was unloading packaged timber. The packaged timber was of different weights. What we tried to get officially with the employer and the TGWU, was a compromise because when a crane came and took a very light package of timber out of the ship’s hold then we would only be paid the tonnage and therefore it would have to go back twice aboard the ship to pick up two of these light bundles of timbers, which amounted for us to a loss of earnings. We met the employers and the TGWU officials over this strike and there was no satisfaction whatsoever. Day after day we were put off until we suddenly decided that we would stop this one particular ship from working until there was a settlement. No settlement came so we visited the ships in the port at that time and the men in the port of Avonmouth decided themselves that they would stop work in support of the men who were working on the Bristol City.

This action was not taken by the unofficial committee at that time, but we were very much there in the background. We were asked after the strike whether we as an unofficial body could do anything to support the strike committee that was involved in that strike. Then the strike got out of hand and Bristol port became involved. The whole port was completely stopped. Avonmouth is about 8 miles from Bristol - Bristol was the smaller port and we couldn’t take the big ships, like the ones which went into Avonmouth at that time. The strike went on for a whole month.

In the unofficial action, we had a secretary and a chairman who was also elected as the public relations officer. I used to deal with the TV, newspapers and radio. At that time there was much bitterness in the strike. Tim O’Leary who was the docks’ official of the TGWU throughout the country was invited to come to Bristol to hold a mass meeting at the Colston Hall to get the strike resolved. We felt at that time that we could have dealt with the situation ourselves so, although this mass meeting was published in the evening newspapers on TV and on radio and was to be held at the Colston Hall, we as an unofficial liaison committee were holding a meeting the same morning. In a way we did this deliberately because it was a very clever move. We were holding this meeting about 2 miles away from the Colston Hall and thought we could draw the majority away to our meeting. Then we decided we would be defeated if we did this because there would be a vote taken at the Colston Hall for a return to work. If we weren’t there, we would have to accept the vote of a return to work. So, we immediately stopped our meeting and over 500 men went to the Colston Hall to attend the mass meeting. We already had a stooge in the Colston Hall to see what was happening when we weren’t there. That stooge was my brother who was a member of the unofficial liaison committee. When we all went to the Colston Hall he explained to everyone what had happened - the committee had just arrived and Tim O’Leary was going to open the meeting.

The meeting started with O’Leary on the mike. He said that he wouldn’t keep us a minute but he would explain one or two things. He started off by saying that he had been invited down to Bristol to resolve the situation and get people back to work. Then he talked about the Bristol City. He said he would go and meet management and fix a new rate of pay as regards package timber coming in to Bristol. He felt certain he could get a new deal. It was a trap that he was laying in order to get a quick vote to return to work and I could see it. So, I went down to the front of the Colston Hall and asked him if I could have the mike to address the meeting. He said, ‘No’. So, I addressed the meeting without the mike and explained to the rank and file that it was only a catch of Tim O’Leary’s to get the men back to work. Was he prepared to negotiate a new rate for package timber for this particular ship that was on strike? He said he hadn’t said that, but that he would fix a new rate for package timber coming into the port. I said that we were concerned over the ship that had been on strike for a month now and explained the whole situation at the mass meeting. As a result, the mass meeting walked out 3 or 4 minutes after Tim O’Leary opened the meeting. 1,200 men - the entire force of the port.

I felt at that time that I was becoming responsible not only for the dockers but their wives and families, because after this meeting we decided we would hold an unofficial meeting. On the way to that meeting, there was an old docker who said to me, ‘Jack have you ever thought what might happen if we put it to a meeting that we would go back to work if the whole situation of wages, conditions, facilities in the port was looked into? Why don’t we try this?’ So, we held a mass meeting and I put this thought of the old docker to the meeting. Would we take a vote on a return to work if there was an enquiry into the whole setup of the docks, the wages, conditions, canteen, toilets and everything concerned with the port. To my surprise there was a majority vote of a return to work on condition there would be a local enquiry.

Narrator: I remember you once said you got a great sense of power from being an unofficial leader and could hardly wait for the next chance to bring out a mass of dockers.

Jack: This is true, because when I was the leader of the unofficial liaison committee I had power. There was a time during the strike when I was asked if I would meet a gentleman who had come to Bristol purposely to see me about the strike. At that time there were leaflets being handed out by the university students. This man who came to Bristol said he wanted to see me outside Bathurst Hotel, which was a public house right by the dockside. So, I went there to meet this man and shook hands with him. He said that he was a member of the communist party. He asked if I would be prepared to accept financial aid or would I accept aid from outside the port by which he meant support from other docks in this country where we could have had a national stoppage at that time.

My wife came into this because she is a Catholic. My whole family is Catholic and when he introduced himself as one leader of the communist party I thought quickly. ‘This is where the communists are trying to infiltrate the port’. They started this in many ports of this country. Jack Dash - a well-known communist - went to Russia every year for his holidays, self-taught communist, and I had the feeling then that this is where the communist party was trying to creep in to the dock situation and the strike that we had in Bristol. I said to this man immediately ‘I don’t want any help whatsoever from the communist party. We will deal with the problem ourselves.’ And we did. And we went back to work. But when we went back to work the feeling was very bad because we had asked for a local enquiry into the whole situation.

I was walking down the quay wall one morning and was met by Mr. Brown an interviewer for BBC TV. He said to me, ‘Jack I see you have got your enquiry but it is not a local enquiry, it is a government enquiry, and it is being called by Ray Gunter, (Minister of Labour).’ This became a little frightening to me, to know that there was going to be a government enquiry because it had been said that I was mingling with the communist party. I knew this was untrue, but the enquiry came about and I was asked to attend. It was held in Bristol, in Clifton, and I attended it with the secretary and the chairman of the unofficial liaison committee. We went back to this enquiry 3 times the same day. The enquiry officer didn’t believe what we were telling him about the part we had played during the strike and before the strike.

The head of the enquiry was Mr. Flanders, an Oxford don. The full-time union officials were brought in as well as the management. We have always been known in Bristol as a pilot port. What happens in Bristol happens in many other ports of the country, but Mr. Flanders was a very clever man during that enquiry. We asked him if we would get a copy of the enquiry. He said that if it was private we wouldn’t, but if it was made public then we could obtain a copy from the government stationers, which we did. When the results came out we received the copy and found to our surprise that, not only was the unofficial liaison leaders partly to blame, but also partly to blame were both the employers and the official trade union leaders. So, we had a kick in the pants, each and every one of us. He was a very clever man because, if he had blamed the unofficial liaison committee at that time, then we would have had a national stoppage of the ports of our country because Jack Dash was ready to support us.

Jack Dash did a lot for the port workers of this country. He first thought of the 11 point Charter that we had in opposition to the Devlin scheme. We knew about that 11 point Charter that came about because we were going to operate it in the port in Bristol. There were some good points in the Charter, but there were also bad points But what it did was it put some kind of a thinking into the mind of the Devlin scheme. I supported the Devlin scheme although Jack Dash was against it because he said it was an employers’ scheme. I could see the good points in it. I could see in it guaranteed work, guaranteed wages, pension schemes, sick schemes. There were things in that Charter we never had before in the ports of this country, and we grabbed it. We were the first port in this country to accept the Devlin scheme and to operate it. That is why we are a pilot port. We gave a lead to the country as regards accepting and putting into operation the Devlin scheme which exists today.

It was surprising what came out of the month-old strike. I became chairman in a union that I had fought against for 28 years. It came about because of a change of heart. I met a man one day in the docks, a total stranger to me, and he talked about the strike. He said he was interested in the ports of this country, and he asked me if I ever went to see plays. I said” I never saw a play in me life.” So, he invited me to go to Bath to see a play called ‘Wilberforce MP’. Now I had never seen a play in my life before, so my secretary and chairman said why not the three of us go.

One of them was Albert McGrath, a great friend of mine. We used to work together before we had an unofficial liaison committee. If we had a stoppage of work and McGrath held the platform he would always look to me for support, and if he could get my support he knew that I could get the support of the majority. He was a very clever character, who was, I believe, a member of the communist party at one time. He was on the dynamite squad in N Africa when they were fighting in the desert in the last war . He was in Popski’s army in Egypt. I believe he was a good soldier, but he was a good docker as well. Albert very often told the story about the problems he had at home. I think it used to get on top of him and he used to bring it into the docks and into some of our meetings we held in the unions. He was a great character and well-liked.

The other man was Bill Stone, one of the top port workers in Bristol. I was responsible when I was forming the unofficial liaison committee to get Bill Stone on the committee because he was not only strong as regards his leadership, but he was also strong in the arm. You need strong-armed men physically as well as mentally. I made Bill my target and he became the secretary of the unofficial liaison committee. Then we had McGrath who was the chairman, and myself. So, we had it all well-organised.

It was a very funny evening when we three went to see this play. We were picked up in a mini car, so there was the driver whom I had met at the docks. Albert was in the front, Bill and me in the back. We were all good smokers and this mini was absolutely black inside with smoke. We were going along and there was a bit of language flying as well, so Albert just leaned over the back and said, ‘Now be careful because I don’t think these people swear,’ so any rate we arrived at the theatre in Bath to see this play.

Wilberforce was a man that was responsible for the ending of the slave trade and in Bristol, of course, we used to deal with the slaves many years ago. I was not very well educated but I heard that Bristol was a big place with regards to slavery many years ago. I knew that Wilberforce had something to do with doing away with slave traffic. During this play my two friends were keen on watching the play but I couldn’t understand a word. I couldn’t understand anything at all about the play. I had never seen a play in my life before but the thing that struck me was after the play was over we were invited in for a cup of coffee. My two friends enjoyed the play very much and I was asked what I thought of it. I said, ‘I am very sorry but I don’t understand the play.’ but what struck me during and after the play was the people that were actually in the play. I met them afterwards, and I was struck by their care for people. Who would want to come and shake hands with an old rogue like Jack Carroll? Here were actors on the stage, pleased to meet me, wanting to know about me, and wanting to help me, to introduce me to people. They also introduced me to an employer in the port who happened to be at the same play. I hated the guts of this old employer but there was I shaking hands with him at this play. It was very amazing to me. We were sat having coffee there and we talked.

I came home from that play and my wife asked me what the play was like. I told her about the whole evening. Somehow I don’t know why, but it started a change of thinking in myself. A change of caring - I started to care for the family more. I started to care for my wife more. I used to love going to the bookmakers of a weekend and having a good bet on the horses. Very often I used to lose and then on the Monday I would have to ask my wife for money to go to work. This used to bring problems into the family with regard to the family housekeeping money. There were one or two little rows that we had over it. But then I started to think, ‘Well why don’t I care more for my wife and family? Why don’t I do something to help them?’

I have a daughter who is 27 now. She resigned from the police force and is working for Rank Xerox, she is married. Her husband is a fireman. I have a son who is in the entertainment business, a comedian and singer. The family are a very close-knit family. I think I would be right in saying that we have a family more together now than we had in 1965, through my change of thinking.

I met a man in the play called Don Simpson. He had a big part to play. I became very friendly with him because he was a man who cared. I never had anyone to care for me in my life. I have always had to care and fight for myself. Then I was introduced to another man who invited me to go to London to an industrial conference. Being in all sorts of trouble in my life, I thought at least I could go to this industrial conference in London. I told the unofficial body that I had been invited to it and invited them to come too. They said they wouldn’t go themselves but said it would be a good thing if I went. So, I went and it was held in the Caxton Hall. I have never seen so many people in industry at a meeting as I saw at the Caxton Hall. There were trade union men, some fulltime men, shop stewards, leaders of unions, people from industry, all sorts of people from all walks of life. The meeting was over the weekend, on a Saturday and a Sunday. I was very interested in the Saturday meeting. Then I was invited to stay in one of the London homes by a man that lived just outside London. His name was Blyth Ramsay. I went to stay with Blyth Ramsay on the Saturday evening and once again I learnt about caring for people, the way Blyth and his wife and family cared for me on the Saturday evening and the Sunday morning at breakfast time. They shared some thoughts that they said they had from the Almighty God, which I was very interested in.

Then we went off to the Sunday morning meeting. At 11 o’clock I was listening to a speaker who had come from Coventry. His name was Les Dennison and he was a plumber. He told a story about how he had been a member of the communist party for 25 years and fighting what he thought was the greatest revolution in the world. He told this story which stuck in my mind, about his communist days, about how he met this force called Mory-Arment (sic), how it changed his thinking, how it reunited his family. He told this complete story there and I was very taken by it. I thought to myself that I would like to see this fellow after the meeting. After the meeting I sat in the corner and we talked quite a bit. He went further into his story, how he had been a party member, about his wife Vera. Then he talked about his son Karl, whom he had named after Karl Marx. I thought to myself, blimey what a revolutionary that man must be to call his son Karl! Then he told the story of how he kicked Karl out of the house because he wanted to marry a Colonel’s daughter, or a Major’s daughter or something and then he met this force of MRA, how it changed his thinking, how he invited Karl back into the family. It was a fascinating story. Then he talked about quiet times, listening to the Almighty God of a morning, how it gave him his thinking for the day. He asked me if I would like to try a quiet time, just the two of us. We sat and were quiet and Les came out with some thoughts he had but I had nothing at the time.

I was pleased about the whole weekend. It seemed to refresh me. It seemed to put new thinking into my mind. I arrived home on the Sunday evening and my wife, of course, very concerned about what was happening with me, asked what happened in London. I said, ‘I will tell you about it tomorrow morning.’ But the next morning I was going to try this first time of quiet time, as Les was talking about. I was up about 5.45 in the morning. I had a white poodle dog and I had trained him to drink tea of a morning. I poured myself a cup of tea and the dog got a saucer of tea, and so we sat there and drank our tea. I had a piece of pencil and paper out. I shall never forget this morning as long as I live. I sat there for quarter of an hour, 20 minutes, had nothing written down on the paper, nothing whatsoever. So, I thought to myself, being an ignorant old docker, ‘well perhaps I am too early’. Too early for the Almighty! I had nothing written down on the paper at all.

I made more tea, I had more tea, the dog had more tea. I had this piece of paper again and suddenly I wrote down, ‘See trade union leaders’ and underneath ‘See employers’. Nothing else whatsoever. Off to work I went and the first person I saw was my friend Bill Stone, who was the secretary of the unofficial liaison committee. ‘Here I have been to London, I enjoyed the weekend and I had these two thoughts this morning.’ ‘Rubbish’ he said. ‘Chuck it away, it is rubbish.’ I thought of Les Dennison and I thought to myself, ‘well I am going to follow this through, just to see what happens.’

The first man I saw in the docks was Tom Davis who was my dock’s group secretary. I hated the guts of this man. I had hated him for many years. I used to work with him as a docker before he became a fulltime union official. I went up to him and I held my hand out and shook hands with him. I simply said to him, ‘Tom, I am sorry for my hatred.’ He looked at me and asked if I was all right, then said ‘You had best come into the union office.’ We trooped in and I told him the story of the weekend. He asked what I wanted to do next and I said, ‘Well I am going to follow this other piece that I have got written down here - see employers.’ He said, ‘I think this is going to be very difficult but any rate, try it.’ So, he rang up the employer who was the biggest employer in the docks in Bristol and also my employer, Mr. Lovell.

He said, ‘Mr. Lovell, I have got Jack Carroll here and he would like to come over and see you.’ ‘No chance,’ Mr. Lovell said. ‘No chance whatsoever. I don’t want to meet Jack Carroll. I saw him on TV during the strike, I read about him in the newspapers, I heard him on the radio and he worked for me as well. I don’t want to know him.’ Tom said, ‘Well I think it is most important that you should meet him, even if it is only for a couple of minutes.’ Mr. Lovell then decided that he would meet me. I went over to his office and saw his secretary. She invited me in to the room and said Mr. Lovell would be there in a minute. In he walked. I stood up and said, ‘Good morning sir,’ I held my hand out and said, ‘I am sorry for my hatred towards you over the years. Most importantly during the strike. I would like to work with you to answer some of the problems that face us in the docks today’ and told him my story about the weekend.

News of this got to Ron Nethercott, my top union official. He is the area secretary who controls about a quarter of a million workers in different industries and the top man in Bristol and Avonmouth. He telephoned me and asked if I would go to Transport House. I went and the secretary said Mr. Nethercott would be there in a minute. Ron was a man that I had hated as well. He was rather good-looking, Ron, he had a big moustache and I used to say some very nasty things about him on the television. I nicknamed him ‘smacker-chops’ because he had this big moustache. He came in, I shook hands with him, and I said, ‘Ron let’s lay down the bayonets. Let’s work together to answer the problems that face us in the docks.’ I spent a whole hour and a half with him. We talked over the problems and he asked me what I thought he should do.

At that time, elections for officers were coming up in the port. I went to a branch meeting and was surprised to find that I was voted chairman in a union that I had fought against for 28 years, the biggest branch in the docks of Avonmouth and Bristol. I was put there by the rank and file, by many of the people who had put me there as their unofficial leader. They heard of my change, that I had stopped gambling - and I was a good gambler. They heard that I had stopped drinking. They heard that I stopped smoking. They said, ‘What’s up with this man? What has brought this change about?’

My change brought many changes in the port. Mr. Edney, the port manager, invited me over to the dock office where we sat and talked over the problems and what we could do about them. Then I became a district committee member, where I used to meet Mr. Edney and many of the employers, our dock officials, our shop stewards and our members of the committee and we ironed out many of the problems. After a year, Mr. Edney came on TV and said openly ‘Through a change of attitude between management and labour there has been more done in the port in one year than had been previously done in 30 years.’ This meant a lot to me because I used to meet and work with Mr. Edney and if we had any problems then I would go to him and sort them out.

We still had little problems in the port. At one time there was a ship stopped in the port and the full-time union officials tried to deal with it. They couldn’t solve the problem, so then it goes to what we call an arbitrator. The arbitrator is a man elected by the rank and file. The employer has his option of electing his own arbitrator. When this arbitration came about, I found to my surprise that I was elected to arbitrate on this particular ship that had been stopped. I had to go with an employer to arbitrate and get the ship back to work. When I was going aboard this ship with the employer he stood on the deck and said, ‘I can’t see any problems or why the men won’t work.’ I said, ‘You won’t see it from up here. You will have to go down into the hold.’ I should imagine it was the first time an employer had been in the hold of the ship to see the conditions the men were working under.

At last, we went down. We looked at the problem and I could see it was a very awkward stow on each side of the ship. I explained the situation to him. He said he couldn’t see why the men couldn’t work it. I said, ‘As you know, it means a loss of wages, it is going to be longer to do the job, if you could give them some payment for it ...’ He said, ‘We know the payment that they are asking for and we are not prepared to give it.’ So, I said, ‘Now listen, if you and I don’t agree this arbitration it goes to an umpire and the umpire’s decision is final. They could get more or perhaps they could get less but let’s go up on the deck and talk about it.’ So, we went on the deck and we talked about it. Now I said to this employer, ‘Can I leave you for a few minutes, go to the forward end of the ship and have some thought about it, because I have just met this force of MRA and it meant a lot to me to have a quiet time and really think out a problem?’ So, I went to the forward end of the ship and I sat down on a coil of ropes. I had no idea what to ask for, for the dockers. I said to the Almighty God quietly, ‘Well I don’t know. Perhaps you could help me.’ Simple as that. I had one or two thoughts about it and I came back and said to the employer that I had worked it out in separate groups - the crane driver, the hatch tender, the men down the ship’s hold and the men on the shore. He said, ‘OK let’s have it’, so I gave it to him. He thought for a minute or two and said, ‘Well it is more than what the employer was prepared to give and it is not as much as the men ask for but I will agree on what you have come up with. I have only agreed on one principle, and that was that I met you before we came aboard this ship. You talked about your weekend in London, meeting MRA, I know that Mr. Edney is very interested in what you are doing in the port and this is why I have agreed.’

The point was I then had to go to the rank and file who were in the canteen at that time and tell them what the employer and I had come up with. As I walked into the canteen one of the most militant there said, ‘Come on Jack, come out with it, what have we got?’ So, I told him what I had got for the crane driver, for the hatch tender, the men in the hold and the men on the shore. He responded, ‘There you are! I told you when you elected Jack Carroll as your arbitrator you wouldn’t get what you wanted. I knew it, because Jack Carroll has got more experience than many of you here and he knew it was too much you were asking for. But at any rate we will accept it, Jack’ he said, ‘and I want to say thank you very much for the way you have done it.’

I went out to the employer who was waiting outside and told him it had been accepted by the membership. That was officially done then, through the unions and the employers, and the ship started work. It worked through the night and it went the next day. This is the kind of thing that I am grateful for and for what I have learned from MRA as regards a change in thinking.

I had the thought from the Almighty God one morning to take on the ports of the world, because I say that people that become responsible for the ports become responsible for the nations and I was invited to Australia and New Zealand, Singapore, Ceylon. I visited all the major ports of the world except in China and Russia. I have learnt a lot from my travels around the ports of the world and I believe that we in this country, in the trade union movement, have so much to offer. Just like the Irish did many years ago when they took Christianity to the world, we in this country took the trade union movement to the world, and today we very often act as though the trade union movement never existed. I believe, although I am 65 years of age now and retired, I still have a great part to play in industry in my country and also answering many of the problems that are facing us in the world today.

I am very concerned because we in this country in the trade union movement don’t know what effect it has in many other countries of the world. For instance, I was in Indio, (sic) where I was invited by Rajmohan Gandhi, the grandson of the Mahatma, and I visited the port of Calcutta and Bombay and many other industries. While I was in Indio, there was a big meeting going on in the House of Commons and I think Enoch Powell at that time made a big speech about immigration. Now that speech that he made at that time went like wildfire out to Indio while we were there. The dockers in Bombay said they would not handle any British shipping after what Enoch Powell said in London. 100 London dockers marched with Enoch Powell on the House of Commons as regards to immigration in this country. I was in Bombay at the time when the decision was taken by the Bombay dockers that they would not handle any British shipping, and also this went to Calcutta. Calcutta said the same - so you could see what effect a decision that was made in this country had on a country like Indio.

We told Mr. Kulkarni, who is the leader of the Bombay dockers, that 100 London dockers wasn’t speaking for the majority of the British dockers in that speech. Only 100 men went and we had 30,000 or 40,000 dockers at that time in Britain. We had a mass meeting and it was said then that we didn't support what these 100 dockers had done. With our meeting with Kulkarni and the dockers in Bombay, they decided then that they would stop the boycott on British shipping. As I said, we don't know what effect we have when we make a decision in this country which affects many other countries in the world like Indio.

At that time, we were so pleased that we were in India when this thing happened that we sent back a message to this country, to the leader of the TGWU in London and he respected it at that time, that people in India resolved a situation that could have affected many ports of the world.

I think change is a very hard thing to accept, especially for the old ignorant dockers. I can remember a few years ago when the dockers didn’t want roll-on and roll-off traffic, that’s where the low loaders come down the side of the ship and all the mechanism goes in to unload it. They thought it was going to be a reduction in men and they wouldn’t be earning the wages. We had a mass meeting in Bristol when we were going to receive our first ro-ro ship. The men were in uproar over this, ‘we are not going to have this, we are not going to have that’.

I spoke at the mass meeting and said, ‘Why don’t we give it a trial? We aren’t going to lose anything by it.’ So eventually this ship came in, and it was manned by six men only. Otherwise, if it had been an ordinary cargo ship, it would have been manned by about 80 men. Now these six men went in with forklifts and unloaded the ship. It was the first time the ship had ever been in to this port. I wasn’t only concerned and thinking of the six men, I was thinking of the trade it was bringing in to the port. We are a municipally-owned port. It is owned by the ratepayers, so it was the trade it was bringing in to the city. We unloaded this ship without any trouble at all and we found that this ship started to come in every week and then we found we were getting two ships a week. We were getting more trade coming in to the port. We were employing men that we never employed before, although it was only six on one ship and six on another, that was 12 men employed who had never been employed before. We were getting the trade and we were quite happy. This was something new. It was a change that we didn’t want to accept, but if we can think about how it affects our industry and our country and the whole world, because we were bringing in trade from other countries. So, we were quite happy.

I think the problem in industry today on all sides, on the trade union side and on the side of management as well, is the fear. I think that we have got to overcome that fear in industry today. On the trade union side, the fear is about manpower or in regard to conditions. I think management as well have got to overcome the fear that faces them in industry today. If we can overcome this fear then we are going to overcome a lot of the problems that face us. You know that we had to accept automation in the ports. This is one of the things that we feared very much. ‘What was going to happen to the docker?’ was the first thought that we had. We had meeting after meeting about what would happen to the docker. We had to accept this new method of unloading and loading ships, containerisation, palletisation, low-loaders, roll-on traffic.

These were fears that we had but if we were going to take our rightful place in the world today, in the docking industry of this country, then we had to overcome this fear and accept automation. We had to reduce the great number of dockers in this country. How were we going to do it? Were we going to do it through natural wastage? We used to have old dockers, over 65, 70 years of age working in the docks. But the time had to come when we had to say that, when a docker is 65, then he would receive a reasonable pension. If we had men who had been injured in the industry then we would have to see that they had been compensated. If we had to lose men, then we said that we would have to train them in other industries, which we did do. We found jobs for these people. Nobody suffered. We didn’t have one redundancy in the docks when we accepted automation. We had voluntary severance pay schemes. We had all sorts of schemes going but never did we have one man made redundant because we overcome the fear that automation was coming in the docks. We had to deal with it, whether we liked it or not. And we dealt with it.

When we become responsible for our industry, then we become responsible for our country and in turn we become responsible for the problems that we have in the world today.

I can remember after the 1914-18 war, the depression and the General Strike. I have seen thousands of people waiting outside factories, perhaps for one job. I have seen the power struggle that has been going on in this country for many years. Now I see that the power has changed hands. The power has gone from management into the trade union movement. The thing that worries me most is how do we use that power in the trade union movement to answer not only the problems of this country but also to help to answer the problems of the world, e.g. - the unemployment situation. I think there are around 800 million unemployed in the world today. I was thinking of the starving millions around the world. I was thinking of the refugees. How do we responsible trade unionists take on to answer these problems? I feel the power that the trade union movement has today could be used in a way to answer these problems.

(lots of high thoughts about people being responsible - not typed out)

We all know there are fiddles today. I used to be a good thief on the docks. I always had a good larder. My wife could go into the cupboard and get all different sorts of meats, because I was fiddling. I believe these are the kinds of things that we have got to change the thinking of people. I was working in the ship’s hold when I decided to change my thinking and give my life to the Almighty God. The dockers that I was working with knew and understood my change. They knew I became a changed man.

I was working down in the ship’s hold with some dockers one day and I knew very well they were going to open a case and pinch stuff. I knew it very well but when they saw me looking at them they battened down the case again and they said, ‘Sorry Jack, we didn’t know you were here!’ Just as though it would have made any difference to me, but the point I am trying to make is that I became an example to people. I used to curse on the docks, then I decided I wouldn’t curse any more. I was working on a ship one day where these men was blaspheming away and they realised that I was there and said, ‘Jack, we are sorry, we didn’t know you were here!’ You become an example. And I think this is what we have got to do today. Become an example.

I was born a militant and I will stay a militant. I believe Jesus Christ was a militant. I only wish we could get more militant employers. I only wish we could get more militant government men. When you become militant it gives you the inspiration, the guts and the courage to fight to put right what is wrong. When we talk about militant you have got to be militant in the right thing. I think that if we could get some good militant journalists it would be good not only for this country. It would be good for the world. A militant is a man who is fighting to put right what’s wrong, in the right way. And this is what I am going to do for the rest of my life.

During the strike in 1965 I was very friendly with a man in the communist party. His wife was a Catholic and my wife was a Catholic, so on Sunday mornings he used to make it his business to come to my house for his wife to go with my wife to the church and then we would talk business. My wife knew this man was a communist but this man also knew that my wife was a good Catholic. I don’t believe his wife was really a Catholic. He used his wife to go to church with my wife so that he could work with me to plan meetings, because I nearly became a communist. I was invited by them to become a communist member.

I go to the Catholic church now. I was in Caux in Switzerland when I was listening to the Almighty God in the quiet time of a morning and it came clear to me to go to church with my family every week although I wasn’t a practicing Catholic. So, when I came back from Caux that year my wife said to me, ‘Well what have you come back with this time? Because every time you go to Caux you come back with something.’ I said, ‘Well, I had the thought that I would go to Mass with you and the family every Sunday.’ I have done that.

Caux is a place up in the mountains. I became interested in it when I first visited it because you meet people from all walks of life - the rich, the poor, the black, the white. I have been at Caux when we have had people from communist countries there. It is a place where you can sit together, plan together, how to answer the problems of the home, of industry, of the country, in fact problems of the world. There are people there from all over the world. You meet the management, the ordinary shop steward, the fulltime union official. It’s a place where you can plan together how to answer or solve the problems that face us.

I had the thought last year when I was there to take a planeload of people to Caux from industry. I did this on real faith and prayer because I had no idea where the money was going to come from to take a planeload of people. I came back and met many of my trade union friends up and down the country and out of meeting them we have made it possible now on August 4th this year to take a group of men from industry to Caux. I think there are about 120 going from Great Britain. I am looking forward to it very much.

On finance: - I was invited to Australia by Jim Beggs, who was President of the Waterside Workers, the dockers, in Melbourne. He was responsible for my fare and my keep while I was in Australia. Then when I was going around there and into New Zealand I met many other trade union men who became responsible for my stay there. I went on to Singapore and Ceylon as well and my fare was paid by one man when I was in Australia. I went to see this man and went with a man called Claudio Falcao. He’s a black fellow from Brazil and a militant man from Rio de Janeiro. We were in Australia and we had the thought to meet a man called Tom the Cheap. This man was the manager of some stores. We went to see him and told him why we were travelling around Australia and New Zealand and our thought about going on to Singapore and Ceylon. He asked how we were going to raise the fare. We said we had the thought to come that morning to tell him our story and what we were hoping to do. He said, ‘I am going to pay your fare to Singapore and Ceylon’. And he did. Of course, we had our return ticket.

We went on to India, and it was fascinating meeting a man like that. Old Tom the Cheap needed a certain amount of change, but we gave him a part to play in our plans. Our plan was from the Almighty God, as I told this man, Tom the Cheap. And he thought he had a part to play in it, and that’s what he did. He got his name because he had a big store there and used to sell stuff cheaper than any of the other small shops could do it.

While I was away and not earning, my family was looked after by ordinary people - schoolteachers, nurses, many from industry. I had some support from the docks as well at the time. They looked after them the whole couple of months I was away. They used to take food parcels and they used to pay the rent. They used to come and take the family out and the family lacked for nothing. This was financed by ordinary people that knew of my change and my work and what I had to give to the world. They became responsible for looking after my family while I was away and I was grateful for it.

My wife, Sadie, gives me 100% support, thank God. I was invited to Indio a couple of years ago, it was at Christmastime. Now you can imagine what it is like going to another country and leaving your wife and family behind at Christmastime, with all the Christmas gifts going around and all the Christmas fare. My wife supported me, and my son said, ‘Never mind Dad, we can have Christmas when you come back’. I went to India for a month and travelled around India with several other British trade unionists. I am grateful for my wife, my daughter and my son, for their support in my travels.

Reggie Holme, narrator: We have this new Pope, John Paul II, suppose you were to find yourself in Rome one day with him, what would you like to say to him?

Very difficult question, but I would say to him that I feel that he has done more, I would say, than any other Pope. I think he has united people from different parts of the world. Many Catholics around the world know the Pope but they know this man as a person, himself. I think he has won the hearts and the minds of many people. I think he has given a lead to the Church. We need the Church, doesn’t matter whether we are Catholic or Protestant or Salvation Army or what. We need the Church. I think more than that we need the Cross, and I think this is where we are falling down.

RAE Holme: What does the Cross mean to you?

The Cross to me is Christianity and I believe that each and every one of us can be a Christian in our own right, with whoever we meet, with any other religion, or with any other politic, or any other colour or creed. I think that the Cross means to me that we all have a part to play under the Almighty God in answering the problems that face us. When I talk about the problems, I talk about the problems in the Church as well. I think that the Church is more united today than it ever was before.

With special thanks to Ginny Wigan for her transcription, and Lyria Normington for her editing and correction.

英語