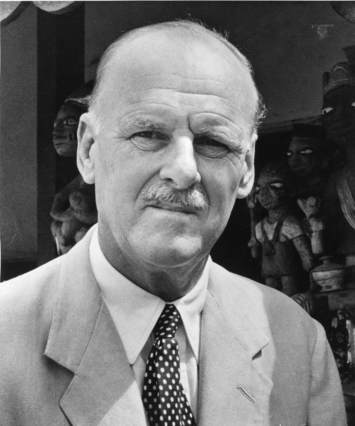

RAE Holme: I am talking with Lionel Jardine and his wife Marjorie, both of whom have had many years in India at the time of the British Empire. Lionel himself was one of the ‘pro-consuls’ of that Empire, in responsible positions in it. The Jardine family had many connections with India - ‘Jardine’ was a name to conjure with there.

Lionel Jardine:

My father had three brothers and all of them served in India. They had great talents. My father rose very rapidly in the Service and one of his brothers became a High Court Judge in Allahabad at the age of 32 and then died of cholera. Another brother died in his 30s of cholera also. That brother was the grandfather of DR Jardine, who captained England at cricket.

Two of the brothers survived and retired. My father went into politics. He was made a Baronet and was offered a peerage. I say these things to show the quality of my father and his brothers.

I was one of six brothers and all of us served in some capacity or other in India. The last of us was my nephew, Sir Ian Jardine, who was ADC to the Governor of Bombay, Lord Clydesmuir and also to the Acting Governor who was an Indian. He got on very happily with the Indian Governor and the Indian Governor’s wife, as I have heard from them.

My wife’s father was a civil engineer who made a railway from Quetta into Afghanistan. Her grandfather was a full General and a hero of the Indian Mutiny.

My furthest back ancestor on my mother’s side was an officer in the Honourable East India Company’s service and landed in India in 1806.

Of the six brothers, I think I was the only one who had the qualifications for going into the Indian Civil Service and I knew that my father hoped very much that somebody would follow him to India. Then I was commissioned at the age of 18 in the Territorial Army and my regiment was sent out to India in October 1914, after the outbreak of the First World War. I spent a few months in India then before we went to Mesopotamia. My regiment was then for 5 years in an Indian brigade. We were the British regiment and there were three Indian regiments so I was very much in the Indian atmosphere.

We were fighting the Turks. It was supposed to be the defence of the oil fields in Persia but gradually it developed into much more than that. We were thinking of moving up to Baghdad and the Turks were thinking of moving down to Basra. It was the beginnings of battles over oil.

We were stationed at one moment on the Euphrates and were ordered to go to the relief of the people who were in Kut. That was a great incident, the loss of an army in Kut which was on the Tigris. So we were moving up probably to make a diversion and were opposed by the Arab tribesmen. In that engagement I was actually hit by nine different bullets fired from various collections of Arab weapons. That ended my time there for a while but I rejoined my regiment again later on and we moved up to the taking of Baghdad. Then on up the Euphrates and we destroyed the Turkish army.

I came home. I took a modified exam for the Indian Civil Service, because all knew so much more. We were no longer schoolboys and we knew an awful lot but we were not in practice for exams. They had references from university (I had been an Exhibitioner at Wadham College and it was assumed that I would have got at least a 2nd class Honours degree and things of that sort), and I have no doubt my war record and my family.

At any rate I was selected, posted to Lucknow and went out.

I had missed an awful lot, of course. I missed three years at Oxford all of the education and the fun and no doubt feminine society and so on. It was very strange to come back into social life again. My mother took me to a tennis party and the first person I saw there was my future wife striding across the tennis court towards us. My mind said, ‘That is the girl I want to marry’. And so it was. She had lost her only brother who was killed at Ypres in 1915, so it was rather a big business for her to leave her family and come out and join me in India. But they had a tremendous Indian background also and they knew what it was. However they were not awfully pleased. Despite this she came out on her own, by ship, and joined me a year later. We were married in Bombay, then joined my post in Lucknow.

The British were beginning to realise that their time had come to an end and each person had to make the decision whether he would take a proportionate pension, to which I was not entitled. If you had done 6 years you were entitled to that and go or to stay on. In fact my first boss, when I reported for duty said to me, ‘Hello, what are you doing here? We are all just going home.’ Which was not very encouraging.

In fact the British civil servants still had a further 25 years or so to run until Independence. But at the time when I arrived to take up my post in the Indian Civil Service we didn’t expect that. The officials didn’t expect that. I find that Lord Linlithgow, when he retired from being Viceroy about 1940 something, still thought we were going to be there for at least another 30 years. But that proved to be a mistake too. It was an unwelcoming atmosphere. I once said to Gandhiji that it was a pity that some of his people had not been a bit more friendly to me when I joined the service, but he laughed at that as being ridiculous.

Because we were there, there was an assumption that we were superior to the Indians in the Civil Service. If that was not so, why were we there? Somebody had to run the show. We were doing it and there were very few of us - there were about 800 of us for about 500 million people. In the first year of our marriage, in the absence of my boss who was up in a hill station, there was terrific flood and civil disobedience and everything you could think of. Knowing nothing I had to pretend that I was in full command of the thing. That went on all through my career. There was a great deal of bluff on our part but we had to do the job. We had to deal with riots. We had to deal with disasters of all kinds. We had to do it with very little physical support - a stick in our hands and a bit of acting.

I coped because I was a public schoolboy. I had been a Captain in the army, I had fought and been wounded. I didn’t hate Indians - I never hated Indians - but yes, I certainly generally speaking felt superior to Indians.

Marjorie: I don’t think I had much interaction with the Indians when I went out there. I was occupied with my house and servants and amusements. I don’t think we came into much touch with them.

Lionel: By 1934 I had been in many important posts. The most recent one was to deal with Hindu-Moslem troubles in Kashmir where there was really civil war and I was called in to deal with that. It was very difficult. I had to straighten out my relationship with the Maharaja and with his Indian high officials, with the Hindus, with the Moslems, with the police and all these things. Which I did but at considerable expense to everybody’s feelings, including mine. I was exhausted and beginning to realise that there was something missing in my life that I needed. I didn’t know what it was. I came home on a year’s leave - which is unusually long. We had a great time and hunted in Ireland, which we tremendously enjoyed, and we saw of course all our families and so on.

And then one day we were invited to an conference of The Oxford Group in a London hotel, in Northumberland Avenue, where we met people, British and American, who seemed to have a totally different attitude to life. They were ‘givers’ and they made me realise that I was a ‘getter’. I was tremendously impressed and wanted to discover the cause of the difference. They told me that they listened to God. I decided that I would experiment with this. I told God that I was very unhappy, that I thought something was missing in my life, that I wasn’t certain whether he existed or not and that I wanted help. I got a response which I felt was him speaking to me. From that moment my life changed. I began to take a genuine interest in God and in what he wanted rather than what I wanted. As you can imagine, my whole life changed from that moment.

I asked God what there was in my life that was keeping him out and he answered. I knew that he had spoken to me. Then after a day or two I asked again ‘What do you want me to do?’ The answer I got was that I should tell my wife some of the things that I had told God, which of course I did not want to do. However I decided that there was no way out of it and I must do this, and I did. That was the beginning of something totally new between us. That was in 1934 and it is now 1979 Between those two dates we have done everything of importance together. As time goes by, more and more we do everything jointly.

Marjorie: I was brought up as a Christian and I confirmed but it didn’t really mean anything to me. The 4 absolutes of honesty, purity, unselfishness and love which we heard about at the Oxford Group houseparty struck me because they were absolute standards and that made me think of my own standards. I realised first that if everybody was absolutely honest in the world, the world would be a new place. If everyone did their bit perfectly and honestly, we should have a new world. So the question was, ‘did I want to be part of the new world - was I willing to reassess my standards?’ This I did, and God helped me to put right the things that I felt I had not done well in. This gave me assurance that there was a God and that he would speak to one and would help one. That is how I started.

When Lionel was in this very depressed state, I then had no answer for him at all. I had felt it was no good my staying at home and being miserable also. So I went out to enjoy myself and bring back some sort of enjoyment into the house. But, of course, that didn’t work at all. It only made a great gap between us. So I saw that going off to enjoy myself had not improved matters.

Lionel: What happened was that after this meeting and so on, we had a common purpose. The next thing that happened was that Dr Buchman suggested we should return to India and live differently. I had been thinking of leaving India and finding a job in England - I didn’t really want to go back at all.

I had six weeks before I had to go back to India and my leave was up. During that time I began to see new visions of what life could be like, run on a different basis. They told me that I would have to create my own team by persuading other people that my ideas were the right ones. A very strange thing happened - as I went up the gangway onto the ship I heard an officer say, ‘Well back we go to that bloody country’. I found myself saying, ‘Well I don’t really feel like that. I am rather interested in going back.’ Another officer came to me the next day and asked what I had meant. It turned out that he had got into the habit of smoking, which he simply could not stop. I said, ‘Well it is a funny thing but one of the decisions I have made is to stop smoking. I didn’t regard it as being very important but perhaps it is more important than I think.’ That man began to get on to the same line of thought as myself with great results later on.

Back in India I came to a new post, as Deputy Commissioner of Peshawar, which was really a very important post at its level. Peshawar was a large military station. There were four different brigades in my civil jurisdiction and it was also the headquarters of the Governor and the Parliament and all this sort of thing, in the Northwest Frontier Province, next to Afghanistan. The Khyber Pass starts, you might say, in Peshawar on its way to Afghanistan. It had a great record of murders - I think it was 600 a year in my district. Something like 2 a day.

The whole of the Momun tribe, which is greatly involved in the present disturbances against the Soviets, were in my control. The fact is that the tribesmen and all Pathans, as they are called, dislike being ruled by anybody. You have to do it in a different way. You have to persuade them. I could tell you many stories about that. They are Moslem and they are quite religious but they have their own ideas about how Islam should be run. Many of them live in an area where there is no authority, so every man is equal. There are no judges, no police, and that makes a lot of difference. They have to take things into their own hands.

When I went on tour, a good deal of which was by motor car, we had military roads. My Pathan driver used to enjoy pointing out to me the places where British officers had been ambushed and assassinated or kidnapped. He liked to see what the effect on me was of this. On the new system on which I was living, I had decided not to take weapons with me. I felt that I was not going to kill anybody. I would leave it to God to protect me. I was not going to shoot anybody, whatever they may do. One of my predecessors always carried a box of bombs in the car with him and every year there were one or two murders of British officers just like myself. So it might have happened to any of us.

The people I worked with watched me. The ‘bazaar’ watched me. My Clerk of Court had been my Clerk of Court in a junior position, so I felt I had better tell him what had happened to me in the intervening years and my new way of living. He broke down and wept. He said, ‘When I was with you before I hardly troubled to collect my salary because of the money I made through bribes. I did this to get my son through university.’ Which he did. He got his degree and in a couple of years time he died. Then my Clerk said, ‘I felt I had sinned in taking bribes and lost everything.’ Then I knew that in future I had a non-bribe-taking Clerk of Court. He no doubt told others and particularly the lawyers noticed a change in me. I had apparently been considered very autocratic in the past. Once in the middle of the night I woke up and remembered something I had said in court. I had said to a barrister, ‘I expect witnesses to be fools. But I expect something different from the bar.’ When I woke up, I found God was telling me that he objected to this. I got up and I wrote a letter and at dawn I gave it to a messenger who took it to the barrister. This was revolutionary. The moment I had done it I wished I hadn’t. But nothing was ever heard of that. It was like a stone thrown into a pond. But when later they said that I had changed from an autocrat to a true servant of the public, I realised that was a very big thing. This was openly said by a man who later became Chief Minister so people knew these things were going on.

Later the most violent anti-British congressman suddenly arrived at my house and attacked me. He had been in prison and so on and advocated violence to the students in public speeches. By that time I had learnt not to try to win the argument but to try to win the man and we parted on a fairly friendly basis and he said he would come back again. In due course he came and he said, ‘I am wondering how it is that you have so much caring in your MRA team. I have never seen such caring.’ I am told he went off and bought a copy of the New Testament and was intending to underline every sentence that had the word love in it. Eventually he resigned from the violent group called the Forward Block and wrote a letter to the Governor saying, ‘I find it incompatible with the standard of absolute love that I have adopted’. In this way, without our doing very much about it, the idea of listening to God began to spread and we would have a team of say 60 people who would meet together in my garden.

It was a very mixed group. We had a Brigadier and we had private soldiers. We had nursing sisters who in the past had only spoken to officers and never to other ranks and all sorts of problems of that kind were overcome as well as larger problems. We had 2 or 3 MPs and barristers. One barrister claimed to be a practising Moslem but told me he had 10 blood feuds. I rather questioned whether the two things were compatible. After some discussion he wrote down the 10 names and he said ‘I will take them in this order and see if I can make peace.’ This was unheard of. He left me and my home and after half an hour he rang me on the telephone and said, ‘When I got home the first man on the list was sitting on my veranda. This is an absolute miracle. We haven’t spoken to each other for 10 years and I had not arranged it.’ Great things like that happened. And of course all sorts of domestic things - husbands and wives and so forth.

It was a mixed district, with Hindus and Moslems mixed in the population. This was a great problem. In my time it was underlined when a row arose about the ownership of a Hindu temple in the heart of an almost totally Moslem population area. It was really about the dues which people paid to the temple. It was a money affair, I had advised them to go to a civil court and they had refused to do that. Then one day the Governor asked me what I was doing about this. He felt it was a very sensitive affair. A few years earlier we had had very big riots in the city in which the trans-border tribal Pathans had taken over control of the city for a few days, which was a very serious matter. But I went with my wife through the process of asking God what we were to do about this problem. The thought we had was that we should do nothing. I told the Governor that I was not thinking of doing anything. There was rather a pause and then he said, ‘Well, it’s your job and you must do what you think is right and I will back you up.’ But I felt he was rather dubious and it was probable that he got different advice from the police and the military. This situation went on for two or three weeks which were times of great anxiety to me and my wife but in the end the leaders of the trouble got to me on the phone and said, ‘We had expected you to make arrests and we had many people to bring in by bus, plus a brass band to bring in from 200 miles away, but as you haven’t done anything, we can’t do anything.’ And so it was settled.

As the years have gone by I have seen how brave the Governor, Sir George Cunningham, was when he allowed me to take the line that I proposed. I think he really understood that I was listening to God. What my wife and I were trying to do was distinctly revolutionary. Some people liked it and some did not. I pay great tribute to the Governor for this matter.

One of the most interesting things that happened was that in June 1939, just before war broke out, Gandhiji passed through the Frontier on his way to Kashmir. My Indian friends who considered that I was ‘different’, to use Dr Buchman’s word, asked me if I would like to meet Gandhiji and they took me along. I was shown in to him sitting in an old army hut. We had a great conversation in which we didn’t altogether agree. He took the view that I could not have changed, because the government could not allow a British officer to change in the terms that I used. He said, ‘If you decide to love me, which you will have to do, then you will have to love all Indians. And equally if I decide to love you, I should have to love all the British, which is absurd.’ And we parted on that note.

But some months later he sent me a message saying, ‘I have had your claims investigated and I find they are all true. If character can be changed, then no problem is without an answer.’

Up in the Frontier, without my assistance, the Indian members of our team of 60 formed a force of their own to deal with communal troubles. They issued a programme and went to the place where the trouble was likely to occur and made speeches. These were men of prominence - MPs and one of them became Chief Minister, the Speaker of the local Parliament, and a High Court judge. This was something that had never been heard of before. They called themselves the Peace Brigade and they signed a declaration which they distributed widely, calling upon people to change and to listen to God. There were Hindus, Moslems, the Indian Christian headmaster of a school in Peshawar - men of much standing in local society. I think I must have moved away about that time as I have no real memory of what happened beyond that, but in itself it was a revolutionary historic thing to happen. There was no rioting - whether as a consequence of this I cannot say, but there was no rioting.

My next posting was as Resident for Baroda and the Gujarat States, during the war. Baroda is an important state 200 miles from Bombay. The Resident is a diplomat. He resides in the state, like an ambassador, but has no authority normally. But if something happens and say the ruler dies and there is only a minor official, then the Resident has to come into operation. The Chief Minister of the State was a very distinguished Indian who had been given two knighthoods by the British crown and he had to come to see me every Tuesday and tell me what was going on. He was older than me, cleverer than me and a very distinguished man. At our first meeting he began to tell me of what happened when he first joined the Civil Service. He did not join the Indian Civil Service, he joined the local one, which was all-Indian.

As a brilliant young man, first class honours from Madras University, he was given a list of British Civil Servants on whom he should call. He called on the first one - who might be called Mr Smith - who showed him quite clearly that he didn’t welcome Indians into the Service at all. Mr Smith said, ‘What I can’t understand is why the British government wants to send me Indians, when there are plenty of young Englishmen at Oxford and Cambridge who would be only too glad to come out and do the job.’ He told me that this interview had left him so bitter that for years his motivation had been to show the British that he was as good as any young Englishman and better. I said to him, ‘If you are still bitter it will come between us and we will find it very hard to work together. Do you still feel bitter?’ After a pause he said, ‘I suppose I do.’ And I said, ‘If you will allow me to apologise for the British and for myself, for our insensitiveness, would that help?’ After that we worked together in great harmony and were able together to do things of considerable importance.

In the Princely states I found things were more difficult than on the Frontier. I found there were defects in myself. All of us in the Service in India cared about promotion and about honours and we cared about knighthoods. I had thought that I had got free from all those sort of ambitions and I told myself that I just wanted to obey God. But I found it was not so simple. Your power to get things done depends a good deal upon your position in the official hierarchy. In the middle of it all a brother of mine arrived straight from two and a half years in a Japanese prison in Burma, where he had been captured and where he had barely had enough to eat and practically nothing to clothe himself with. He laughed at my ambitions and my feelings about promotion and so on. That made me take a fresh look at mysel, and to decide forever that I was not interested in anything except what God told me to do.

Six weeks after I first met Dr Buchman I had to go back to India at the end of my leave. Those were the days when one went by ship. I remember at Victoria Station I was seen off by a friend and I was thinking ‘I am going back to India. I am going back to take a revolution. I don’t know anybody in India who has ever heard of Dr Buchman or his work. What shall I do?’ And my friend said, ‘You will have to change people and make your own team.’ This didn’t particularly cheer me up. However, as I went up the gangway to the ship, an army officer said to me something like, ‘Back we go to that bloody country’ and I felt moved to say to him, ‘I don’t feel quite like that. I am rather excited at the experience.’ He didn’t make any comment on that.

A day later another army officer came to me and he said, ‘What did you mean when you said that you were rather excited at going back to India?’ I told him about this change in me and that I had made this decision to live differently and I was wondering what that was going to turn out like. Ln fact I didn’t go back to Peshawar, which was the place where everybody knew me. For the time being I was posted to a very remote area called Bundale Kund which was all Maharajas and tigers. The place where my Residency was had a small army training school with a few British officers. It hadn’t occurred to me at that time that my change had anything to do with Indians. I thought it was for Christians and British.

I found that they were all going on a long recess of two months and that I should - as it seemed to me - be alone in the station. However I found there was an elderly, not to say old, American missionary lady. It happened that she had only done one unselfish thing in her life, which was to adopt a Canadian baby and he had grown up in time to go to the front in France and be killed. I was the same age as that boy would have been. She was tremendously interested in me partly for that reason and partly because of my Christian and spiritual aspect of change. She had found it very hard going with the civil service to get them to be interested in what she was doing. Largely she was looking after the descendants of the famous ‘Thugs’ of central India, who had all been hanged about the time that she came to India as a young girl. She had found she had to set up some organisation to look after their children’s welfare.

We became great friends. I learnt a great deal from her and she learnt something from me about the new way people were getting the truths across in Britain and elsewhere.

Then I had a recess myself of a month in the very hot weather in the hills. I went up to where Dr Stanley Jones, of America, who was the leading missionary of his time, had what he called an ashram which was frequented mainly by missionaries and some Indians. He welcomed me because he felt I brought new ideas for the benefit of the missionaries. One thing I discovered was that a great many missionaries were not on good terms with the only other missionary in the place where they resided. Dr Stanley Jones suggested to me one day that I go and see the Colonel of a Gurkha regiment, which were in barracks in the hills. I should say about 110 miles away from his ashram and I took this on,

Colonel Channer, who commanded the 3rd Gurkhas, had a distinguished military career behind him and later became a Major General. His wife was religious. He was rather a retiring personality. They listened to everything that I had to say and we then had a rather controversial discussion. I spent one night with them and then returned to Dr Stanley Jones. Within a few months Channer had been transferred to command the brigade in Peshawar and I had been transferred to be Deputy Commissioner there. Our houses were actually on opposite sides of the road. By that time he had progressed a great deal and we began to form a team. In fact, he amongst other things became very acceptable to the leading Indians in the station, which was not always what happened with the military commanders.

Towards the end of my time in India - 1944 - I was given short leave in England. For a good many years we had not been able to go on leave because of the war. We had to remain in our posts in India. I was held up in Bombay for a few weeks waiting to get a passage. During that time a friend and I called on an old friend of mine who was Postmaster General of Bombay. He told us that he had a very unpleasant situation on his hands. The postal workers and sorters were threatening to go on strike because their pay and conditions in wartime were not adequate. He said the danger of this was that the railway workers would probably join in the strike and possibly the dockworkers. This would have a very harmful effect on the war effort made in Bombay. He didn’t know what to do about it. We asked if we might be permitted to be present when he met the men’s leaders. The leaders of the workers in India generally were not workers themselves. They were quite likely to be lawyers - in this case the leader was a tough barrister and I should think he was a Marxist. The atmosphere when we joined the conference was extremely cold. Then I was introduced by my name of Jardine and the men’s leader said, ‘Are you any relation to MR Jardine?’ And I said ‘Yes, we are cousins.’ He said, ‘I was in chambers with him when I started my legal work and I always remember his great kindness.’ And the atmosphere then warmed up quite a bit.

My friend then said that he suggested that the discussions were based on one or two principles - one was ‘people before things’, and the other was ‘not who is right but what is right’. The men’s leaders, rather to my surprise, gladly accepted this proposal. The end of the discussion was that the Postmaster General would meet the workers in a big meeting and would tell them what he was thinking about and what his proposals were. This I gathered was a very great advance. Probably no Postmaster General had ever spoken direct to the men.

In the meantime we had been making enquiries about the holidays that the postmen were entitled to. It seemed that a postman was entitled to one Sunday off in every three, if he could get it. It also seemed that their pay for wartime was not adequate and not comparable to other jobs in Bombay. I was staying with my brother who was working with the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in Bombay. He was very angry when he heard that I had got mixed up in something which he felt had got absolutely nothing to do with me. However, the meeting with the men was a success. The Postmaster General said he was sorry that he had not taken the trouble to find out exactly how the war was affecting them and promised to do something to get them better pay and conditions.

Soon after that, a shock came for the Postmaster General when he was informed that a committee of enquiry was coming from Delhi to find out about the pay and prospects and general conditions of the workers in Bombay. The man they had chosen to be chairman of this commission was a former Marxist leader who had been in prison for an attempt on the life of an English judge. By that time Communism had become quite respectable as the Russians were fighting on our side and leaders who had been imprisoned had begun to be released. However, the Postmaster General did not think that this man was a suitable person to head the enquiry. To my surprise he asked me - an Englishman and someone who had got nothing to do with it - to be with him when he received the Marxist chairman. So we received him in the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay. When I was introduced as being in the Indian Civil Service he gave me a look of great distaste. But we began to talk and I told him about some of my experiences and my new relationship with Indians and so on and he was obviously impressed.

The Postmaster General then invited him to a teaparty, which was to be a house-warming party as he was moving into a new house. To my surprise the Marxist accepted the invitation. At that party we had the editor of The Times of India, one of the Governor’s ADCs from the Coldstream Guards, a missionary and his wife, and one or two other people, mostly British. We told stories about our adventures in India. At the end the Marxist got up and said, ‘I cannot leave here without thanking you all for you have said today. It will make me reconsider opinions that I have held all my life.’ We could hardly believe our ears, but this was true. He was a great leader amongst the textile workers of cities like Kanpur and Ahmedabad and he went back and was instrumental in bringing about an agreement between management and labour where there had been bitter strife which lasted for some years to come.

I became a friend of his and learnt a great deal from him about things that I knew nothing about. He eventually came to the MRA conference at Caux in Switzerland and was the means of bringing many eminent politicians and others to that place, including Mr Nanda who later on two occasions acted as Prime Minister of India, and Mr Jagjivan Ram who at this moment might become the next Prime Minister of India.

I say this to give an idea of the change that took place between 1934 and 1944. I arrived in 34 not knowing of anybody who had heard of the Oxford Group and I ended up with something that was a great force having an effect upon the great problems of India. I am glad to say that force, greater than ever, is still at work, particularly in politics in Delhi, but also in all aspects of life in India.

I came back to England finally in 1947 with the permission of Field Marshal Lord Wavell who was then Viceroy of India. He knew I was going to join Dr Buchman and the work of MRA. After a few years we decided to make a great sacrifice and sell our home in the country and come and live in London. This was a great sacrifice for my wife who loved the country, her garden and her parents’ home which she had inherited. If she had not been willing to make that sacrifice I could not have done it.

Thereafter we were free to go wherever we felt God wanted us to go. This took us all over the USA, for instance, and it took me later all over Africa - partly because I took the only white-man part in a film called ‘Freedom’ made in Africa, written by Africans and acted by Africans. That film is still going strong and I am told it is compulsory viewing for all policemen in Nigeria. I went with it, at its first showing in Capetown for the members of the Legislative Assembly, and heard afterwards that it made a deep impression upon the white leaders of South Africa. I believe that was the beginning of a change in the attitude of the white people to the black, which is steadily going on to this day.

I am now 85. In 1972 I went with the film to its first showing in Papua New Guinea, in the local language, Pidgin. I was present in the open air in a stadium where the screen was put up and the film was shown. 40 MPs were present. They all came up to me after the show and said, ‘We are so glad you are alive.’ I couldn’t quite understand what they meant. The point was that they had seen me on film and they thought I was an actor not a real person who had been through these experiences. This also happened just at the time of independence and is said to have had a tremendous effect upon public opinion in Papua New Guinea. All the MPs asked for the film to be shown in their constituencies and a young Scotsman from Glasgow took it mainly by canoe all over the country

I feel tremendous gratitude for the privilege of being in these great events which are now coming to fruition. The political climate of the world is such that all responsible people must seek an answer, wherever they can find it, to our perplexities and lack of leadership. I feel convinced that my own country, with its Christian heritage, is bound to give a lead to the nation in taking on the responsibilities that Dr Buchman saw so clearly at that time when he suggested that we should live differently. I feel that it is not impossible that the leaders of all the political parties in this country should admit that human thinking is not enough. Common sense is definitely ‘out’. That they must start as a habit to ask God to tell them what they should do in all the difficult decisions that they have to take. I believe Britain could give a lead to the world on these lines - not as imperialists but as humble Christians.

Long ago William Penn, of Britain and America, told us that men must choose to be governed by God or they condemn themselves to be ruled by tyrants. This is even more true today than it was when he said it.

Marjorie: I remember when a party was held to say goodbye to Lionel in Peshawar. Many of the notables of Peshawar were present and the Chief Minister gave the farewell address. In it he said, ‘We have known 2 Mr Jardines. One we will draw the veil over. The other Mr Jardine we are very sorry to have go, because he has helped us to bring God out of our temples and mosques into our offices and homes.’ This I feel was a very important statement.

Bas. Hogya! (Enough - that will do... in Hindi)

With special thanks to Ginny Wigan for her transcription, and Lyria Normington for her editing and correction.

英語