It is one thing to fight an ideology. The real answer is a superior ideology. At Caux we found democracy at work and, in the light of what we saw, we faced ourselves and our nation. It was personal and national repentance. Many of us Germans who were anti-Nazi made the mistake in putting the whole blame on Hitler. We learned at Caux that we, too, were responsible. Our lack of a positive ideology contributed to the rise of Hitler. (Baron Hans Herwarth von Bittenfeld, from Garth Lean, “Frank Buchman. A Life”, p. 351 )

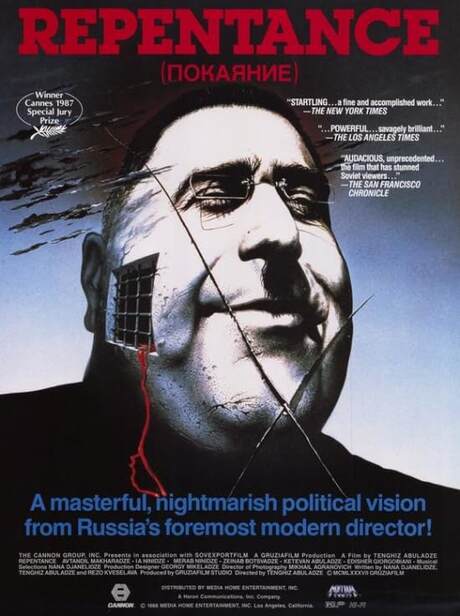

“Repentance” by Tengiz Abuladze was one of the key films released on Soviet screens in 1987 – an event absolutely revolutionary in itself that marked the turning point of that period. It felt almost like “victory of humanism over fascism” in our country. (By “fascism” I mean here the state system of lies and oppression.)

Largely metaphorically, but still very explicitly, “Repentance” revealed the horrors of tyranny and political repressions – the theme largely suppressed in the Soviet Union for more than 20 years, since the dismissal of Khruschev.

In a nutshell, the plot is the following. The daughter of the victims of the tyrannical regime, time and again, digs out of the grave the body of the late dictator and puts it near the house of his family. She is finally caught and during the trial we learn, step by step, the whole history of dictatorship in the city (in the film the totalitarian state is allegorised by one abstract Georgian city). While the dictator’s grandson, a young man of no more than 18-19 years old who is present at the trial, is deeply moved by the story and horrified by his grandfather’s deeds, his parents refuse to confirm the truthfulness of the woman’s words. Towards the end of the film, the boy and his father have a heated debate. Seeing his father’s refusal to recognise the truth, the boy shoots himself with his grandfather’s rifle – a powerful metaphor for the dark past killing the future. Only then does the dictator’s son dig his father out of the grave with his own hands and throws the body down from the mountain and into the abyss.

“Repentance” launched a new epoch in the country. It was followed by hundreds of other films, both feature and documentary, all exposing in their own way the terror of mass repressions and the humiliation of human dignity under the Stalinist regime.

I watched only recently the film “The Law”, made in 1992 by a well-known filmmaker Vladimir Naumov. I was struck by its powerful and uncompromising statement. One of its central characters, a prosecutor, had at some point behaved in a cowardly manner and sanctioned the arrest of his friend, an innocent man. After Stalin’s death, that friend, largely through the prosecutor’s efforts, is fully acquitted. His life though is broken, he lives under a false identity and is afraid to return to his old flat. The prosecutor visits his friend and admits his own cowardice, but is denied forgiveness. Devastated by the enormity of his guilt, the prosecutor shoots himself. And it is only after this striking sacrifice that his friend is capable of regaining his true identity and can really return to life.

Not only films – short stories, novels, memoirs focusing on the traumas of the past – filled the Soviet bookstores in the late 80s and early 90s. All of that was very necessary – the nation had to become aware of its past. People had to learn about the crimes committed by their fathers – or face their own guilt. Victims of the regime had to receive justice.

The ultimate purpose of that painful but cathartic experience must have been to awaken both individual and collective conscience in the Soviet people and encourage them to build a better country. “Never again!” - that was the implied slogan of the Russian “historic truth campaign”.

Tragically, the effort largely failed. The reasons were many, and some of them I discussed in an earlier blog. However one important reason might be the absence of a clear alternative to the dark past. What came to the surface in those years through cinema and literature was the cruelty of the system, dishonesty and corruption permeating all spheres, betrayal and cowardice among friends and family members, and above all, division of the society into the abused and the abusers. Without any positive ideology, most people preferred either to deny or to forget all traumas of the past, while others chose to identify as the victims.

The danger lies in both choices. Victims cannot bear responsibility for the crimes. Those who choose oblivion reject any responsibility since the crimes don’t exist. In either case, no serious processing of the sins takes place, nor new constructive ideology is born.

Western Germany after 1945 could have followed a similar scenario. Denazification (which involved, among other things, showing films about Nazi crimes to all Germans), together with ruined cities, dismantled industry and food shortages might have led Western Germany to become again a militaristic nationalist state. But several important factors made its destiny different, one of them, I believe, being crucial.

“The biggest sinner can become the greatest saint”. This truth that each of us is supposed to keep in mind sometimes gets forgotten. Fortunately, there were people who remembered to put it forward after 1945. The quote above I took from biography of Frank Buchman by Garth Lean, who was citing the cable Buchman sent to Max Bladeck, a German communist who at some point had chosen to join Moral Re-Armament (MRA). One day, encouraged by his not very decent colleagues, Bladeck got heavily drunk and behaved in public in a disrespectfully familiar way. On recovering, he felt so deeply ashamed that he wrote to Buchman saying he was going to leave MRA in order not to tarnish its reputation. Buchman’s loving response, which expressed “faith in the new Max”, led Bladeck out of despair and back to life.

A popular misconception is that forgiveness implies turning a blind eye to wrongdoings or diminishing their scale. But let’s be clear: Buchman was not saying that drinking and hooliganism were not that bad after all. His message was that no matter how deep his friend might have fallen he had the potential to rise again.

When the French choir was singing “Es Muss Alles Anders Werden” to welcome German delegates in 1947 in Caux, the message was that Germans as human beings could still choose a new life and ultimately (perhaps) be forgiven.

When Konrad Adenauer, the post-war German Chancellor who in 1944 narrowly avoided death at the hands of the Nazi, was engaging his people in the work of rebuilding, his message was not that he had forgotten or was downplaying the crimes committed – but that he had faith in the potential resurrection of his former enemies. Resurrection which was not guaranteed but which was possible.

The work of outstanding individuals such as Irene Laure and hundreds of other MRA volunteers in Germany and France, as well as the efforts of churches, the overall strategy of European politicians aimed at reconciliation and integration – all of that created the environment which not only facilitated personal and national repentance, but also offered the superior ideology of hope for everyone. This was something the late USSR and post-Soviet Russia badly lacked.

To be aware of one’s country’s sins and repent is vital for building a different society. But beyond the evil past and miserable present, some positive idea is essential.

If ever history gives us another chance we, again, will have to call our nation to repentance. But just as importantly, we will have to be ready to offer forgiveness. (Suicide of the “bad guys” is not an answer, after all.)

Elena Shvarts, Moscow