A vigorous call for the creation of 'islands of integrity' to combat global corruption was given at the opening of the Caux Conference for Business and Industry in July.

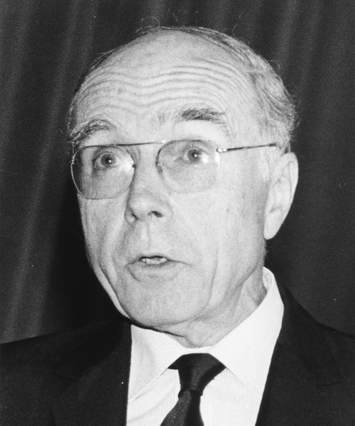

'For a long time we in the West thought that corruption was essentially a feature of Asian, African and Latin American countries,' said Daniel Dommel, President of the French branch of Transparency International, an NGO set up in 1993 to fight corruption in international commerce.

But following the 1973 oil crisis, Western businesses competing for markets in the Middle East 'became accustomed to bribing foreign politicians or officials in order to win contracts,' said Dommel. 'As long as the bribes were paid out beyond our shores, our governments turned a blind eye. They considered this corruption to be of benefit to our economies and employment figures. As it took place elsewhere, it was not our problem.'

Dommel, formerly France's Chief Inspector of Finance, attacked the laissez-faire approach to corruption which regarded it as a necessary fact of economic life in certain cultures. Its fluctuation around the world and throughout history was, he said, ample proof that corruption was not inevitable. It had been largely eradicated in Singapore but grown to a dangerous level in Italy.

Although bribery might bring short-term benefits to a company, such practices led quickly to a vicious circle, said Dommel. Bribes became expected more and more often, and any advantage was cancelled out once competitors began to bribe too. A policy of never paying bribes might carry short-term economic risks, but in the long term a good reputation and the trust this inspired in clients carried considerable economic rewards.

It was wrong to argue that corruption was culturally acceptable in certain parts of the world, he continued. If this was so it would take place openly, rather than in secrecy. 'Corruption is not so much the fruit of poverty and underdevelopment as the sustainer of these conditions, and this is one side of its pernicious nature,' argued Dommel.

On the economic plane, corruption led to ever-mounting costs. On the political plane, it led to a loss of confidence in the government and the elite. On the social plane, the cover-ups required negated democracy, creating a society where blackmail thrived and ultimately rebounding on the initial corrupter.

Dommel underlined the importance of a healthy political environment with an honest system of party financing, a strong judiciary, and a clear moral stance against corruption by all in authority.

In the economic sphere, transparency was of the essence: corruption 'cannot stand the light of day', he said. This involved clear auditing, appropriate market regulations and more effective enforcement, which implied new legislation. The process had to be international, as no individual country was prepared to sacrifice short-term economic competitiveness by implementing more rigorous laws than its neighbours. This was also the only way to improve international judicial cooperation. There had been some progress recently, but it was inevitably slow.

Dommel described the needed 'islands of integrity' as pockets of clean economic practice in either geographical areas or economic sectors.Companies from the same sector might agree to renounce certain practices and adopt accepted codes of ethical conduct. Such agreements would require mutual transparency and an openness to all-comers, in order to avoid the dangers of a cartel.

Transparency International aimed to give technical support to any country, local administration or company wishing to participate in an 'island of integrity'. Public opinion could often play a pivotal role in the fight against corruption, Dommel concluded.

By Richard Jones