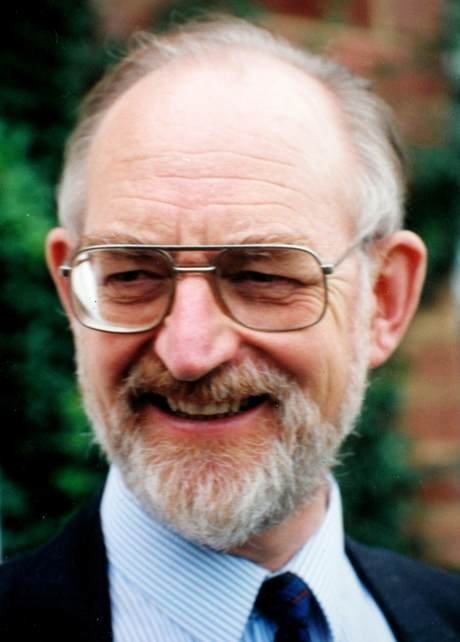

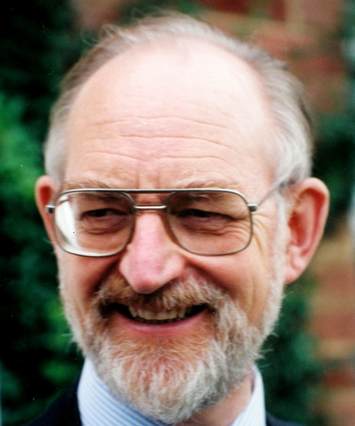

A "peace-builder, who worked hard to maintain, restore and strengthen peace by promoting reconciliation and the peaceful resolution of disputes".

Reconciliation on the Pacific island of Bougainville was a high priority for this quiet peacemaker.

Alan Weeks was, said Sir Michael Somare, the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea(PNG), a "peace-builder, who worked hard to maintain, restore and strengthen peace by promoting reconciliation and the peaceful resolution of disputes".

Somare was referring in particular to Weeks' work before and after the terrible conflict in what is now Papua New Guinea's autonomous Bougainville province between 1989 and 1997. The prime ministerial tribute came in a two-page condolence message read at the funeral of Weeks, who has died after a battle with pulmonary fibrosis.

Weeks was not a public figure. But this quiet, unassuming man with a gift for making friends, left his mark on PNG and especially Bougainville. He participated in early meetings that eventually led to an agreement to end armed conflict, co-operate in restoring peace and work towards further development in Bougainville.

Joseph Kabui, the President of the recently formed Bougainville Government, said: "Alan's unwavering dedication combined with a deep love for his fellow men and women encouraged us immensely in Bougainville in our time of great need to pursue peace for all our people at all cost. We know how much Bougainville was close to his heart until his death."

Alan Burfood Weeks was born to British parents in Kodai Kanal, southern India, where his father worked in a hospital run by the London Missionary Society.

After World War II, in which his father served in the Indian Army Medical Corps, the family returned to Britain. However, his father took up a post in Canada before joining the World Health Organisation, where he became chief of programming and planning for the malaria eradication division.

While their parents were overseas, the Weeks children - Alan, his sister, Joy, and brother, Richard - went to school in England.

Weeks had a spirit of adventure from an early age. He studied at Southampton Technical College, joined the merchant navy as a radio officer and worked on P&O's Asia-Pacific routes. In 1965 he joined the British Antarctic survey and spent a year on the ice shelf manning the radio communications. It was there that he decided to try to make a difference in the world.

Waiting to take up a university place, he attended a Moral Re-Armament conference in Cheshire. It was in the aftermath of the national seamen's strike, which brought ports around Britain to a standstill for six weeks.

People at the conference who wanted to do something about the industrial unrest created a musical review, It's Our Country, Jack.

Weeks contributed savings to buy sound equipment and became stage manager for the production, which, at the invitation of seamen and dockers' leaders, played in 28 British ports over nine months.

He was stage manager for a subsequent production, Anything to Declare, which toured Europe, Asia, Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea. He met Elizabeth Mills, a Melbourne nurse. They married in 1969 and settled in Australia in 1971. In the early 70s they spent more than three years in PNG, where Weeks got to know political leaders, particularly Bernard Narokobi.

Subsequently he made more than 30 visits to PNG and Bougainville.

Working with people in Milne Bay had him well placed to help reconciliation after the Bougainville conflict broke out in 1989. His vision led to the establishment of the Bougainville Trust building project, aimed at shoring up understanding among the divided peoples of Bougainville and the rest of PNG.

More recently Weeks became involved in the Solomons crisis, until his illness.

Narokobi, now PNG's high commissioner to New Zealand, said at the funeral service in Melbourne: "Alan Weeks was a great inspiration to Papua New Guinea, to Bougainville and to the Solomons … a real example of how you can be a Christian and share your life among people of all races and all faiths."

He is survived by Elizabeth, son David, daughter Cathie-Jean, and his siblings.

John Farquharson

This article first appeared in the ‘Sydney Morning Herald’, June 1, 2006

English