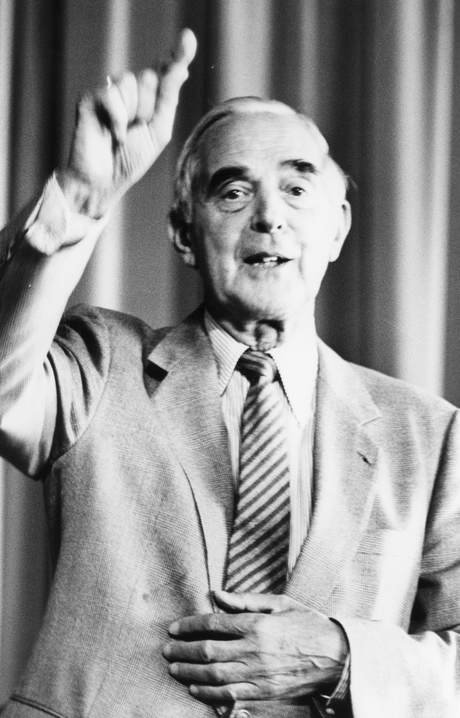

“Figures are important; people are more important.” Such was a lifelong conviction of the Dutch industrialist Frederik (Frits) Philips, who was for 10 years, from 1961 to 1971, the president and chairman of the Philips electronics multinational.

The company, which originally manufactured light bulbs, gave the world a range of products, including the first electric razors in 1938, the first colour TV broadcast cameras, the cassette recorder and, more recently, the compact disc.

The Philips corporation, based in Eindhoven, became Europe ’s largest electronics company. As the company’s Vice-President in the 1950s, Frits Philips oversaw its expansion into 50 countries with sales in over 70.

Yet he was far from being the Left’s image of an exploitative capitalist. Though a keen advocate of free market enterprise, he always saw the Philips factories, especially in developing countries, as providing vital employment and incomes as well as skills and technology.

He could even claim Karl Marx as one of his forebears and Frits delighted in telling business colleagues behind the Iron Curtain that Karl Marx had worked on Das Capital in his grandfather’s home in Zaltbommel. Marx’s mother, Henriette, was the sister-in-law of Philips’ great-grandfather, Lion, who held long political discussions with the young Marx during his frequent visits to Lion’s home. Frits Philips believed that his father’s and uncle’s sense of social concern developed out of these discussions, and Frits wrote, in his autobiography 45 Years with Philips (1978), “We never had the feeling that we were considered despicable capitalists”.

Frederik Jacques Philips was born in Eindhoven in 1905. His father Anton and uncle Gerard had founded a light bulb factory there in 1891. From Frits’ earliest childhood all talk in the family was of “the factory”. He studied at the then technical university in Delft , gaining his degree in mechanical engineering in 1929. His course included working as a lathe mechanic at Alfred Herbert’s machine tool factory in Coventry . During his second year of studies he met “the woman of my life”, Sylvia van Lennep, and they were married in The Hague in 1929.

He joined Philips in 1930, as manager of the Philite plastics factory, which employed 28,000 people manufacturing radio parts. He became assistant managing director of the whole company in 1935 and, when his father became Chairman of the supervisory board in 1939, Frits was appointed Managing Director, under the company’s President, Frans Otten.

Frits’ personal integrity, and concern for the welfare of employees, was strengthened by his introduction to the Oxford Group in 1934, the Christian movement that was the forerunner of Moral Re-Armament (MRA). This became a life-long source of inspiration to him, especially throughout the war years.

When Germany occupied The Netherlands in 1940, Philips’ board members evacuated to the United States, leaving Frits, aged 35, at home in charge of the company’s 19,000 Dutch workers. The company now came under the Reich’s aviation ministry, and he found himself playing an astute game of cat and mouse with the German authorities. It was a situation perhaps unique in industrial history. Frits saw the task as keeping the company together whilst making the least possible contribution to the German war effort. This included deliberately manufacturing faulty radio valves, hiding the capability of manufacturing armaments, and being as unproductive as possible. The company continued to produce light bulbs and Germany allowed Philips to export to neutral countries, which kept the sales organization going.

In 1943 Philips set up a plant inside a German concentration camp at Vught, near Eindhoven. It was on the Germans’ instigation but Frits negotiated the final say on supervision and employment. The plant assembled radio receivers and Philishave electric razors. This gave jobs to Philips’ Jewish employees who had been detained and helped to save their lives. In 1996, Israel honoured Frits Philips with the Yad Vashem medal, as one of the “righteous among the nations”.

The greatest danger came in 1943, as the allied liberation became more imminent and Dutch workers began to strike. The SS arrested him and, as the news of his arrest spread, all the employees went on a general strike. The commanding SS General threatened to execute Philips and other heads of management. This prompted a hasty return to work. Frits was held for five months before being released.

As the allied invasion began in 1944, rumours spread that Germany had a list of senior Dutch whom they planned to deport to Germany . Philips escaped through his office window as German guards arrived at the company. Cycling away, he remained in hiding in friends’ attics and in the countryside till the liberation of Eindhoven two months later. He knew that capture would be punishable by death but he trusted his safety to a divine providence and an inner prompting which seemed to indicate when to change his hiding place. Meanwhile, Sylvia was arrested and held in Vught in an attempt to make him break cover. But her own faith gave her peace of heart and she refused to reveal his whereabouts. She was released just before the camp was moved to Germany in September 1944.

After the war the task of reconstruction began. Unlike France and Germany, the Netherlands remained virtually strike-free in the post-war years, thanks largely to the tripartite Foundation of Labour, involving employers, unions and government, which Frits Philips helped to establish. Fellow industrialists and union leaders had been together under German detention, giving them the chance to brainstorm about the post-war future.

A major influence on Frits’ life and thinking in the post-war years was his regular participation in industrial conferences at the MRA centre in Caux, Switzerland, which had opened in 1946. There he met trade unionists as well as young and budding politicians from developing countries. As a result of these encounters in Caux, a cabinet minister or a civil servant “knew that I was not just a businessman pursuing my own self-interest, but that I had a wider concern which included the development of his country”.

Assuming the company’s helm in 1961, Frits launched television factories in Asia and Latin America, entered into a joint venture with Matsushita in Osaka, Japan, manufacturing cathode-ray tubes, and acquired the ailing British television company, Pye, in Cambridge. During his 1961-71 Presidency, the company grew from 226,000 employees to 367,000 worldwide, while its turnover increased from 4.9 billion to 18.1 billion guilders (£485m to £2.2bn), though profits declined.

When Philips launched the pocket cassette player in 1963, the company shared the technology with competitors, such as Grundig, in order to increase the global market. Philips’ cassette players sold twice the expected numbers. The same was to happen later when Philips shared its compact disc technology with Sony. But Frits Philips was disappointed that the company could not develop an environmentally friendly Stirling “hot air” engine and the technology was sold to a Michigan company.

After his retirement, Frits Philips launched the Caux Round Table (CRT) group of senior European, Japanese and American business executives in 1986. He had been alarmed to read an internal Philips report which accused the Japanese of dumping consumer goods on the western market at below cost price, and he feared a growing trade war. He saw the need for trust building and transparency between company executives. The CRT’s Principles for Business were published in 1994, incorporating the concept of human dignity and the Japanese approach of kyosei, interpreted as “living and working together for the common good”. It was believed to be the first international code of best practice written by such senior industrialists and was presented to the UN Social Summit in Copenhagen in 1994. It has since become a standard work, translated into 12 languages.

A strong family man, Frits Philips was also an avid supporter of PSV Eindhoven football team, founded by the Philips company in 1913, and attended most home matches. The whole of Eindhoven celebrated his 100th birthday on 16 April 2005, naming itself Frits Philips City for the day. The Dutch Prime Minister was one of his visitors. “Haven’t you got anything better to do?” Frits asked.

Frederik Jacques Philips, businessman, born Eindhoven, 16 April 1905, married Sylvia van Lennep 1929 (died 1992), four daughters (one diseased), three sons, died Eindhoven , 5 December 2005.

This obituary first appeared in The Independent, UK , on 7 December 2005.

English