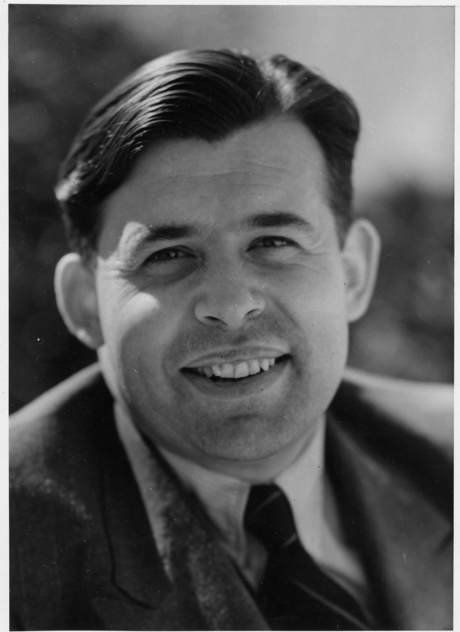

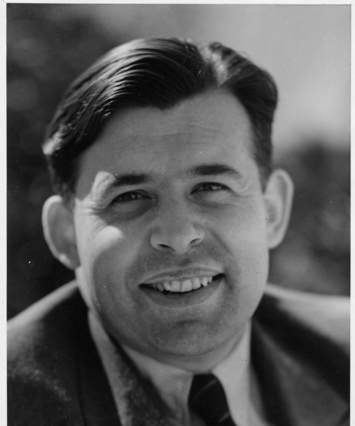

Philippe Mottu was a Swiss in the tradition of Henry Dunant, the founder of the Red Cross. Both men were touched by conflict and acted out of their Christian conviction to promote reconciliation. In so doing they added lustre to Switzerland's peace-making role. As a Swiss Foreign Office official during the Second World War, Mottu was asked to identify and make secret links with German officers opposed to Hitler. Though their opposition proved abortive, Mottu's links with them found fulfilment in his role as the founder of an international centre for post-war reconciliation. It was opened in the Alpine village of Caux, near Montreux, in 1946 and attracted thousands of French and Germans.

Mottu was the son of a Calvinist pastor and came from a distinguished Genevese family who could trace their ancestry back over four centuries. He was a young banker in Geneva when in 1933 'a surprising event' touched his life. Attending a church service for businessmen, he emerged, by his own account, 'having had the personal experience of an encounter with the one who has written on my heart these words: "If any man will come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me."' This led to his studying theology in Lausanne, where his Latin professor, Jules Rochat, told him about the ideas of the Oxford Group, the forerunner of Moral Re-Armament (MRA). 'He talked to me about moral standards by which to test our thoughts and actions, about listening to the inner voice and honesty as the conditions for normal living with the people around us,' Mottu recalled.

Called into the Swiss Army in 1939, Mottu and his colleagues organised a resistance movement against Nazi propaganda. While in the army he studied political science in Geneva before joining the Swiss Foreign Office. In 1940 he was encouraged by a priest to make contact with a German diplomat, Herbert Blankenhorn, who suggested they should take a walk in a forest near Bern. 'There, at the very moment France was falling, he told me how and why Germany would lose the war,' Mottu recalled. Blankenhorn introduced him to a number of his colleagues. In November 1942, Adam von Trott, who had been a Rhodes scholar at Oxford, invited Mottu to fly to Berlin to meet others who would subsequently plot against Hitler. Mottu was particularly struck by his talk there with Hans-Bernd von Haeften, a senior foreign ministry official who was wrestling with the conscience issue of whether or not a Christian should rebel against his government and plot to kill his head of state.

Two years later, and only days after the Allied landings in Normandy, Mottu flew to Washington, supported by the Swiss Foreign Minister and with the encouragement of von Trott and other Germans. Invited to the United States by MRA's founder, Frank Buchman, Mottu saw it as a chance to take his first-hand news of the internal German opposition to Hitler direct to President Roosevelt. But, to Mottu’s pain, Roosevelt refused to take this seriously. Von Trott joined the July 1944 plot by German army officers to assassinate Hitler. The plot failed and von Trott was among those who were executed on Hitler's orders. The news of their failure was 'a terrible blow', recalled Mottu. 'On the one hand I thought of all the friends whose lives were now in danger, and on the other I knew that the war would go on even longer.'

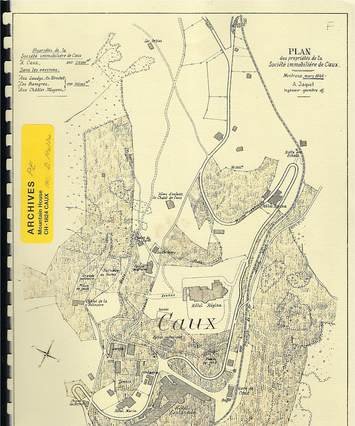

As early as Easter 1942, Mottu had had the conviction that if Switzerland was spared the horror of war it should provide a centre for post-war reconciliation in Europe. He was certain that Caux would be the place. He told a colloquium at Geneva University years later: 'From 1942 onwards an idea germinated in my spirit that if our country escaped the hardship of war and occupation we would have a singular task at the end of the war to contribute to the reconstruction of Europe.' After the war Mottu and two colleagues, Robert Hahnloser, an engineer, and Erich Peyer, a lawyer, acted to buy the former Caux Palace Hotel on behalf of MRA. A splendid Belle Époque turreted building, it had been opened at the beginning of the 20th century as a resort for wealthy Europeans. During the war it was run by the Swiss Army as a centre for refugees, including escaping Allied officers and several hundred Jewish refugees who fled from Budapest in the last weeks of the war. But by the war's end it was in a derelict state, and in the hands of a bank which planned to demolish it. The hotel had run at a loss for many years. Inspired by Mottu's vision, 95 Swiss families contributed their savings to make its purchase and renovation possible.

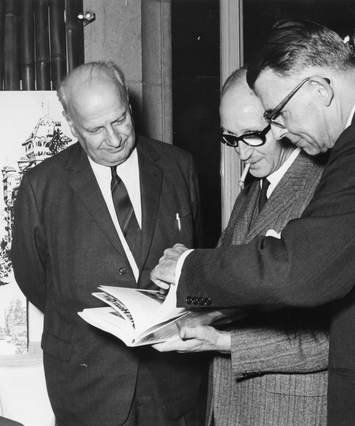

The first Germans to be allowed by the occupying Allied powers to leave their defeated and demoralised nation came to Caux. They flocked there in their hundreds over the four years after the centre's opening in 1946. They included Konrad Adenauer, then Mayor of Cologne, who was to become the post-war Chancellor of Germany, and Hans Böckler, head of the West German trade union congress. The Germans were able to meet in Caux with French leaders, including the foreign minister, Robert Schuman, and Irène Laure, a leader of the French Resistance who was elected to parliament in the post-war intake of MPs. Mottu saw particular significance in Laure’s encounter in Caux with Clarita von Trott, Adam von Trott’s widow. Laure’s eyes were opened to the suffering that German women had endured, equal to that of the French. This enabled her to surrender her deep hatred towards Germany. For Mottu such profound encounters were a fulfilment of his earlier work during the war. Mottu was 32 when the Caux centre was opened in 1946.

In 1996 he gave a jubilee address there. The martyrs and survivors of the July 20 plot had 'played an indirect but indispensable part in establishing the contacts which led to the creation of the conference centre', he asserted. According to Edward Luttwak, writing in Religion: The Missing Dimension of Statecraft (OUP, 1994), nearly 2,000 French citizens and more than 3,000 Germans 'took part in the Caux meetings of the formative post-war years of 1946 to 1950'. Franco-German reconciliation was cemented in the Schuman Plan which gave birth to the European Coal and Steel Community, the organisational progenitor of the Common Market. According to Luttwak, 'MRA did not invent the Schuman Plan but it facilitated its realisation from the start. That is no small achievement, given the vast importance of every delay — and every acceleration — of the process of Franco-German reconciliation during those crucial, formative years.' Others who took part in Caux in those post-war years included the mayors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from Japan. History remained Mottu’s passion. His first major book was entitled Le destin de l’occident (The destiny of the West) and his second was Regard sur le siècle (A look back over the century) (1996), which included a foreword by the former French Prime Minister Edouard Balladur. Mottu was married to Hélène de Trey in 1939.