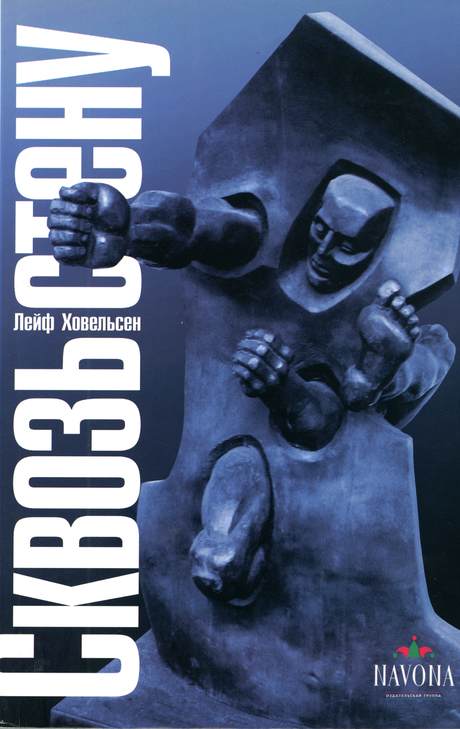

Among many wonderful books published on For A New World there is one which became a “fishing hook” personally for me. This is Leif Hovelsen’s memoirs Out of the Evil Night, whose Russian translation Through the walls the author presented in Moscow back in 2006.

2010 – 2013 was the period when I felt particularly passionate about making my country more democratic and humane. In those years it seemed possible to transform our flawed democracy into a healthier one – we only needed to fix this and that and the system would start working better. Therefore the idea that you will never be able to make a positive change in the society unless you follow in your own life the principles of absolute honesty, purity, unselfishness and love seemed wild and entirely unrealistic. I liked the sincere style of the book and felt solidarity with the author when he wrote about his experience of apology to the enemies. However, all Leif’s vivid examples of how straight behaviour and honest apology helped to transform human relations, families and whole nations were not enough to convince me about four absolutes being the only way. I thought that, generally, it was right to be honest, pure, unselfish and loving at all times, but you couldn’t live by that. You just couldn’t be open and honest with everybody. Recognition of your own flaws to resolve a conflict with an opponent is obviously a good and necessary thing – this was not exactly a discovery - but it won’t work with most people.

Yet, the thought that democracy starts in me and depends on my personal qualities, of which absolute honesty, purity, unselfishness and love are the key ones, somehow stuck deep in me and continued to gnaw quietly at my blemished conscience. It would be an exaggeration to say that I was giving it too much thought, but imperceptibly I started evaluating my behaviour against absolute moral standards. The result was too often disappointing and it discouraged me, leaving me just as skeptical about the applicability of absolutes to real life as before.

It so happened that in 2011-2012 a seemingly-weird family was staying for some months in my friends’ big house, which I used to visit quite often. Gradually I found myself in bitter conflict with both the husband and the wife. The latter would stop at nothing to offend me in different ways, and I, not fully aware of it, retaliated in a similar way. My personal conviction was that the initiator of the conflict was that lady, so the gap widened every time I came to have tea with the hosts.

Finally, they found a new place to live and were preparing to move out. I came to see my friends shortly before the notorious lodgers were to go. It was very likely I would never see them again – what a relief! However, I had an unpleasant feeling in my stomach that I was about to part with the people for ever on really bad terms – and that would be irreparable.

My thoughts wandered to Leif’s story – the way he apologized for his hatred to his enemies. Was this relevant to my case? Was it worth giving it a try? I wasn’t sure. Rather the opposite, I was pretty sure that person was hopeless and my efforts to reconcile would be entirely lost on her.

Nevertheless, I made my decision to, at least, clear my own conscience by recognizing my “10% of guilt” – whatever the consequences. I braced myself, concentrated on the wrong things I had said to her, and pronounced my brief “sorry speech”. The effect was totally unexpected: she started weeping. Through her sobs, words of apology to me began to come out. It turned out that our quarrel had been inflicting her a lot of suffering (I would have never guessed it, I had been sure she was enjoying it). We had a sincere talk that gave us both a feeling of a great relief. Miraculously enough, we parted friends – and not just with the lady herself, but with her husband as well.

With their somewhat vagabond lifestyle, I never met that family again, yet I was left with more than just a lighter heart. I saw that Leif Hovelsen’s method worked. It really did, even with those who I had considered “crackpots”. “We all are human, in the first place, no matter how erratic we may seem to each other” was my thought.

It wasn’t as if “since then I was changed”. As Vreni Guisin once said to me, “we don’t change in one day”. But that episode implanted a conviction in me that absolute honesty about oneself, when wisely put into practice, might work wonders.

The story above is not exactly about myself. It is about a great Norwegian Leif Hovelsen, who went through a dreadful experience of a Nazi concentration camp and got out of it to become “a fisher of men”.

His name regularly pops up in stories of people, sometimes entirely otherwise unconnected with each other. Medical doctor and MRA full-timer in his younger years, Sturla Johnson speaks about his friend Leif Hovelsen who, back in 1950s, brought him to Caux and introduced to MRA. A college teacher and another MRA full-timer, Camilla Nelson mentions him as a dear family friend who lived in the MRA house in Oslo, where she spent her childhood. Philosopher Gregory Pomerants in his afterword for the Russian edition of Leif’s memoirs refers to him as one of his good and very old friends. A University lecturer Olga Z., a widow of a judge of the Russian Constitutional Court, recalls Leif giving her husband driving lessons in the mountains of Norway. An accountant Lyudmila K. shares how much Leif admired their excellent ski grounds near the Vorobyev Hills in Moscow. The list of people, whose life he touched and in whose minds he, as if by chance, implanted some good thought, includes hundreds of names. Particularly long would be the list of us Russians with whom Leif Hovelsen built lasting friendships. Not all of us became visibly changed – but each is certain to change their tone and expression when the name of Leif comes up.

However what really distinguished Leif Hovelsen as an international trust-builder was the warmth and respect with which he used to speak and write about his German and Russian friends, i.e. about those who came from the countries Norway had highly controversial relationships with. I was deeply touched by the sincerity of his admiration for the courage and vision of those Germans and Russians who fought totalitarian regimes at the risk of their lives. Leif Hovelsen was the one who discovered for himself and shared with the rest of the world “the best of Russia”, thus making unique experience of the Soviet dissidents universal moral and spiritual legacy.

I only saw him twice: once in the Norwegian Embassy in Moscow, when he came to present Russian edition of his book. The second time was in July 2011, when I visited him in a hospice in Oslo, together with his (and now my own) friend Jens J. Wilhelmsen, no more than 2 months before he passed away.

Elena Shvarts, Moscow